Ancestry, as a concept rather than as hereditary entitlement, is not an easy thing to talk about in the UK. If a First Nations American or Australian waxes lyrical about his ancient ancestors, he is unlikely to be expected to prove his credentials with a DNA test. In Europe the picture is far more complex with notions of native-ness more difficult to define.

Ancestry, as a concept rather than as hereditary entitlement, is not an easy thing to talk about in the UK. If a First Nations American or Australian waxes lyrical about his ancient ancestors, he is unlikely to be expected to prove his credentials with a DNA test. In Europe the picture is far more complex with notions of native-ness more difficult to define.

At the Oxford Real Farming Conference last month, indigenous farming methods and their relevance today was something of a theme. While the COVID-19 pandemic forced the Conference online, detracting from the many spontaneous interactions of previous ORFCs, it did allow the inclusion of participants from many areas of the world not usually able to attend.

That it is essential to draw upon the deep understanding and reverence held by indigenous people for their ancestral lands could not be more urgent than it is today. In a world of industrialised food production and corporate control, the words of many of the indigenous speakers at this year’s ORFC were inspiring. Who could not be uplifted by Samuel Gensaw in the film ‘Gather’ describing the re-learning of traditional skills as, ’a profound and amazing and wonderful return’. Or be challenged by his question, ‘This is only the beginning: what are you going to say, how did you fight for what you have?’

I was, however, saddened by some of the casual accusations and assertions that went unchallenged. One of these was that there are no indigenous people in Europe apart from the reindeer herding Sami of the Arctic Circle.

I ran through mental pictures of European tribes, from the islanders of St Kilda to the mountain farms of the Pyrenees and wondered how those people viewed their origins? I realised I had never considered myself anything other than indigenous and was almost naively surprised by the idea that other people wouldn’t recognise me as such. In fact, I had to look up a definition of ‘indigenous’ in the dictionary, which stated, ‘People or things coming from the country in which they are found rather than being brought there from another country.’

It would be easy to get embroiled in a debate about genetics and ancient migration routes here, but that would detract from the point of this piece.

Many well delivered pleas were made for the industrialised and disconnected masses to look to the knowledge of indigenous peoples for a route back to a sustainable and connected way of living. I found little to argue with in the view that classical philosophies and organised religion were often used to justify the colonialism at the root of the exploitation of the planet, that led us to the mess we find ourselves in today.

That an aboriginal culture sustained for 60,000 years has much to teach the more recently arrived Australian, should go without saying and Bruce Pascoe’s book, Dark Emu, is a must for anyone seeking to understand how to live on that unique continent.

But what about closer to home? Are we, as Europeans, uniquely to blame for the evils of the world? Do we deserve to all be tarred with the same brush? In truth, I doubt certain speakers at the ORFC were thinking about people like me when they referred to Europeans in such a generalised way. I doubt the Welshman who rails against ‘The English’ has in mind a Pennine hill farmer or that a Northerner who rants against ‘Southerners’ conjures up images of Cornish trawlermen. When ‘locals’ in every village complain about ‘incomers’ they are unlikely to mean the Bangladeshi shop keeper who has contributed so much to the community.

This divisive language is unhelpful in a world experiencing a human driven environmental crisis on a massive scale. If we are to turn our suicidal trajectory around, we will need to listen and learn and greet allies wherever we find them. When we talk in a derogatory way about people that are not ‘us’, it is more often than not due to our sense of being threatened by their presence. Often that sense of threat is real and has been instilled in people over centuries of abuse.

It should be remembered that colonialism and the expansion of empires (not all of them European) usually starts close to home. In the UK, the Highland Clearances and the Enclosure Act took the land from the people as surely as the wholesale land grabs in foreign climes. Ironically, this frequently led to the emigration (and sometimes transportation) of the dispossessed, furthering the aims of the colonists by providing them with a workforce in the distant reaches of their supposed empire.

The displacement of rural communities in the UK continues today unabated. The sell-off of council farms and houses and the extortionate cost of rural land and property, forces people from areas where their families have lived for generations to be replaced in many cases by urban wealth, often in the form of second homes.

I was very fortunate to be born into a community that had retained its cohesion and many of its traditions into the second half of the 20th century. Ironically, the twilight years of the Somerset coalfield, with its unionised workforce and unsightly slag heaps, protected our villages from the gentrification that was already creeping into much of our valley and hills. Many local people worked ‘at pit’ but there were very few that were not also engaged in some form of farming or food production. The vegetable garden of a Somerset miner was never a hobby and the growing and preserving of food was taken very seriously indeed. While the new destructive industry was taken up for the sake of a pay packet, the old traditions of the small farmer remained.

‘Regenerative’ agriculture is often seen as a relatively new response to ‘conventional’ farming. ‘Conventional’ sometimes seems to be confused with ‘traditional’ in the minds of those new to farming or those converting established farms from industrialised systems.

But much of what is considered new is, in fact, very old. Prior to the clearances and enclosures of the 18th and 19th centuries, small intensive arable plots and larger areas of communal grazing were the norm. I believe that much of the method, if not the social structure and land ownership, dates back to the earliest days of farming. The simplistic notion that clear dividing lines can be drawn between hunter-gatherers and farmers in Europe or elsewhere is now being rightly challenged. That the remnants of our ancient sustainable practices have survived the industrialisation of the countryside must be recognised if they are to guide us in the future.

In the film ‘Gather’, Fred DuBray of the Cheyenne River Lakota Nation muses on the fact that non-native people can usually understand the value in bringing back keystone species like the buffalo, but can’t understand the need to bring the culture back. It’s a theme picked up by Scottish singer Brian McNeill:

‘Bring back the wolf, bring back the eagle

But the dark eyed child and the red-haired man

are still gone from the glen.

So why don’t you try to bring back the people?

You just don’t care or you’re too damn scared

To make the Highlands real again.’

I remember as a child being told by an elderly relative that when you drew water from the well you had to pour some back on the ground ‘for manners’. I remember the informal vegetable exchange system that operated throughout the row of council houses built on the common where I felt the presence of my ancestors and found their hunting camp in the potato beds. I feel their presence still when I pick whortleberries on Whort Sunday. I remember my Methodist grandmother’s thoroughly pagan adherence to small daily rituals and the more overt communal rituals of harvest and Halloween.

If I wanted to know about any aspect of the River Chew, I would ask our local mechanic who knew it better than anyone. We all knew where to find crayfish and to be thankful for their presence in our river.

In his book, The Silent Weaver, Roger Hutchinson describes the grass weaving of Hebridean ‘outsider artist’ Angus McPhee: ‘It did not arrive from nowhere. It was the last expression of a craft which had been alive since humans first shared the shores of the North Atlantic Ocean with clumps of marram grass, but which would slip within a single lifetime through the careless fingers of the twentieth century.’

In his book, The Silent Weaver, Roger Hutchinson describes the grass weaving of Hebridean ‘outsider artist’ Angus McPhee: ‘It did not arrive from nowhere. It was the last expression of a craft which had been alive since humans first shared the shores of the North Atlantic Ocean with clumps of marram grass, but which would slip within a single lifetime through the careless fingers of the twentieth century.’

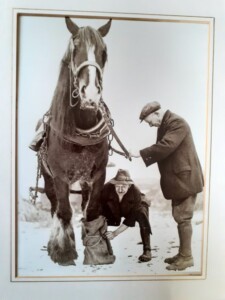

I am reminded of a fine teacher who taught me to spin. As I sat there with the fleece turning to yarn like magic, she made the observation, ‘haven’t you got beautiful hands’. While I looked doubtfully at the legacy of years of hard graft, she told me about two executives that tried spinning as a break from their city lives. ‘They didn’t know how to think with their hands,’ she said, and I saw how she applied the meaning of beautiful. As I look at them now, I see the hands of my grandmother salting beans in glass jars, of my grandfather lowering the branches of our favourite chestnut tree for my younger, smaller hands to reach. I see the berry-stained hands of cousins and aunts and the strong hands of uncles tying improvised snowshoes over the hooves of a Clydesdale horse. I see hands guiding trows on the River Wye and guiding sheep on the Mendip droves. And back in that garden in the village where I was born, I see the hands of my father planting potatoes and, quietly beside him, the hands of our ancestors chipping flint.