While women have always played a vital role in British agriculture in great numbers, the challenge has been making their contributions visible, not just within statistical data but also in terms of representation within farming periodicals, agricultural papers and mainstream media. ‘Building a more resilient and fairer food system involves communication between everyone involved in the complex web of food production,’ she says, ‘we need to develop strong narratives to find solutions to some of our current challenges, gender equality being just one.’

While women have always played a vital role in British agriculture in great numbers, the challenge has been making their contributions visible, not just within statistical data but also in terms of representation within farming periodicals, agricultural papers and mainstream media. ‘Building a more resilient and fairer food system involves communication between everyone involved in the complex web of food production,’ she says, ‘we need to develop strong narratives to find solutions to some of our current challenges, gender equality being just one.’

To celebrate International Women’s Day, we hear from three leading female figureheads in the UK sustainable farming movement on why visibility matters.

Female role models

When we write about female representation in farming, of which 17% identify as female out of 180,000 farmers, it’s important to remember that within this percentage there will be varied opinions drawn from different experiences and intersectional identities. Where one woman may feel alienated by terms such as ‘feminist’, and not view their work as anything extraordinary, another might seek non-binary language to describe themselves. Visual representation, when we get it right, goes a long way in communicating inclusivity and upending stereotypes. In turn, greater diversity strengthens the farming community which will ensure it develops a fairer and healthier agriculture system in the future.

Alice Holden, Head Grower at Growing Communities in Dagenham, grew up in rural Wales in the 1980s and 90s, where she describes the beginning of her journey as a producer. ‘The image in my head was generally an older man,’ she writes. Women were not visible in their farming roles, nor well represented in media, so it wasn’t until Alice began working at Blaencamel farm that she encountered her first female role model, the grower Anne Evans. She writes, ’I don’t think I realised it at the time, but the effect and importance in having someone I could recognise, more easily helped me see I could do this work.’

A lack of visible role models, within any vocation or industry, has negative consequences. Seeing yourself represented is deeply important, as it provides encouragement for new entrants and empowerment for those already working in the industry. Media (articles, photographs and advertisements) are sites of meaning where gender identities are constructed and circulated, ultimately shaping narratives around women in agriculture within public consciousness, and also in how these women view themselves within their workplaces. As Joya says, ‘If you can see women in these positions,’ she says, ‘it’s one step easier for any woman that follows in their footsteps.’

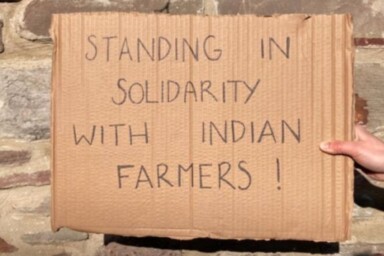

As Dee Woods, food and farming actionist, Landworkers’ Alliance coordinating group member and co-founder of Granville Community Kitchen, explains, the lack of visual representation continues to be deeply harmful. ‘Racialized people, particularly women, have been rendered invisible in the media and within the food system,’ she writes. While the Black Lives Matter movement resulted in media coverage, she points out that since then many [women] have faded away into the shadows of structurally racist notions of positionality.’

As Dee Woods, food and farming actionist, Landworkers’ Alliance coordinating group member and co-founder of Granville Community Kitchen, explains, the lack of visual representation continues to be deeply harmful. ‘Racialized people, particularly women, have been rendered invisible in the media and within the food system,’ she writes. While the Black Lives Matter movement resulted in media coverage, she points out that since then many [women] have faded away into the shadows of structurally racist notions of positionality.’

When seeing herself reflected in the media recently, Dee experienced the full gamut of emotions: happiness and joy in terms of celebrating her work, but sadness and anger too, for the Black and POC women who remain unrecognised. As she writes: ‘There are so many amazing women who should be uplifted and celebrated.’ Seeking out their stories and manifold contributions should be a priority if we want to ensure all those underrepresented in the farming media feel valued and are further supported in their work.

Representation of women working in varying areas, from diverse backgrounds and in different stages of their careers, can only be a good thing. It draws newcomers who see longevity in their chosen career and renews confidence in those climbing the ladder. When Ellen Rignell, of Trill Farm Gardens in Devon, started in organic agriculture in 2015, her issue was not so much the lack of contemporaries but a strange absence of older generations. She noted that this is acute within horticultural authorship and industry conferences. ‘The older female growers I have come across have been inspiring and it’s a shame their stories aren’t more widely known,’ she states. ‘It would be interesting to dig deeper to find some older female farmer role models.’

Searching the history books

While historical events such as the Haughley experiment, started by Lady Eve Balfour and Alice Debenham in 1939, and the Women’s Land Army of the Second World War were documented, offering fantastic opportunities to learn about ground-breaking women such as Amelia King, daily photographic events capturing women at work farming are slim. Between the 1930s and 1970s, representations of farming women were most often located in ‘women and family’ pages in the farming press. A history of patrilineal inheritance meant women were often seen as involved in farming due to marriage and were not celebrated as independent farmers or business partners. But, as Stuart Hall noted, the media has often reproduced dominant ideologies at the expense of alternate views.

As one woman from Oadby, Leicestershire wrote in 1938: ‘The common assumption that the countrywoman cares only about domesticity is not true. Moreover, it is most unfair. There are hundreds of country women today who are working partners. Their husbands know and appreciate this.’

While it would be unfair to say farming periodicals have not been sensitive to the cultural shifts since our Leicestershire farmer wrote her letter, they still have fallen short in painting an accurate picture of women. Carol Morris and Nick Evans have explained that while 1970s media depictions isolated women within the confines of domesticity and feminine attributes, by the 1990s key media had virtually stopped referencing women’s appearance and were starting to visually depict women taking on differing roles, though the breadth and diversity of women working at the time was still largely ignored. There is little research that explores whether or not women identified and made meaningful associations with the role models that media presented to them.

Changing visual narratives

In recent years, the landscape of gender equality in farming has begun to shift once again. In the past fifteen years alone, the number of women listing ‘farmer’ as their occupation has risen 7.7%. These are still low numbers; however, as 64% of the 2017-2018 agricultural graduates were women, we can only expect this number to keep growing.

Several factors have made this possible from global interest in placing women in leadership roles, to industry-specific updates like advancing technology and farm diversification. But an added influence, which hasn’t been widely explored, is the rise of social networking sites that encourage photo-sharing for public consumption. As opposed to relying on media representations alone, these platforms handed women in farming the tools to document their livelihoods as they saw fit.

Several factors have made this possible from global interest in placing women in leadership roles, to industry-specific updates like advancing technology and farm diversification. But an added influence, which hasn’t been widely explored, is the rise of social networking sites that encourage photo-sharing for public consumption. As opposed to relying on media representations alone, these platforms handed women in farming the tools to document their livelihoods as they saw fit.

Photographs populating news feeds and circulating publicly revealed women facing the joys and battles of farming, tending their flocks, harvesting produce. For Alice, social networking sites can offer a sense of community. While she warns image feeds can become siloed, they opened up the door for a conversation around working and motherhood in our current age. ‘Pregnancy, maternity leave and now child care have all brought various challenges,’ she writes, ‘so seeing the stories of others has helped me not feel I am the only one struggling at times.’

As recent research has shown, these image-based platforms have challenged traditional notions of who and what is photographed. Now a diverse selection of women, including those who’ve been marginalised and rendered invisible, have come to the fore and disrupted traditional hierarchies of visibility.

Dee expresses that she is always concerned with the ‘lenses’ she is being seen through. While photographic media is indexical, it is always taken within a social context, and she must consider her accountability and responsibility for the communities of which she is a part. However, the act of self-imaging in the public sphere is something to be celebrated. ‘Being in control of our own narratives means we don’t have to be someone else’s idea of womanhood or motherhood or any roles or gender attributed to us,’ she writes. ‘We can be authentic and tell our stories with all the pain, the joy, fragility, spirituality and respect to our ancestors, elders, communities, our young people and children and the land.’

Photography by Joya Berrow and writing by Ellie Howard.