Knowing where to start in distinguishing good and bad practice in an incredibly complex marine world is tricky. To limit damage on the seas, hand-line caught fishing is best, while it doesn’t get much worse than dynamiting the sea floor (outlawed and yet still practiced in some parts of the world), but what about the rest? The vast majority of fishing lies somewhere in the middle of these two extremes. In this broad ‘grey’ fishing area, there are some practices that are significantly better than others, and consumers need help navigating their way through. In a perfect world, perhaps we would return to anglers catching all of our fish with a rod and line. However, hand-line caught fish will satisfy only a fraction of demand and so risks becoming elitist. It amplifies fishing pressure on the limited number of species that are caught in this way, and just as importantly, does nothing to differentiate between the most damaging fisheries and many of the better small-scale ones, both of which may catch your lemon sole but with vastly different impacts on the marine environment.

Small-scale fishers around the globe face the same problems in varying degrees – access to the fishing areas or to quota, limited days at sea due to weather or seasonality, limited or no access to ice or processing facilities, inability to command control over prices and limited or no presence at policy level. Moreover, once fish from small boats are landed and sold to processors, their catch is not differentiated from those of the industrial boats, making it difficult for consumers to buy fish from small-scale fishers. For the most part, recognisable access to the market, except at the very local level, is non-existent and all traceability is lost. Modern food systems are wasteful and inefficient – they require large volumes of the same species, of the same size, in order to be processed mechanically, so this determines how industrial vessels fish. The small-scale fishers tend to catch a wider range of species in lower volumes and of varying sizes, making their fish inappropriate for today’s industrial-scale food processing systems. This is in spite of the fact that more and more people are now actively choosing to buy ‘local’ or ‘ethical’, taking an interest in where their fish comes from as a result of rising awareness of the degradation of our seas.

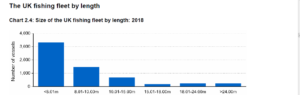

The under 10 metre small-scale coastal fishers that make up 80% of the UK’s overall fleet by number, provide 50% of catching-related employment, often in vulnerable coastal communities, and these fishers land over £110 million worth of fish and shellfish annually. And yet, the small-scale sector has overall access to only 2% of the UK’s fishing quota which when coupled with the demise of many stocks and the inability to fish further out to sea where more economically viable species are often caught (due to the distances they can travel and the danger of weather), has resulted in the loss of many coastal fishing businesses.

Up until the recent past, the tussle between the under 10 metre vessels and larger boats for quota allocation was the main source of discontent in the sector; but of late, the main concern is not the amount of quota (although strong views continue to be expressed on the subject), it is more the fact that there are not fish present on the grounds, in many cases.

The lack of fish on the ground, coupled with the Marine Maritime Organisation’s inflexibility in matching access to fishing opportunities as species move from one catch area to another, has meant that the under 10 metre boats are catching only around half of their annual entitlement, and we are losing small-scale fishing businesses to the detriment of coastal communities around the country as a result. The figures speak for themselves: the total number of fishermen employed in the UK has fallen from just under 50,000 in 1938, to around 20,000 in the mid 1990s, to less than 12,000 in 2016. In 2016, there were 11,757 fishermen – a decrease of 350 since 2015.

Work has been done by the New Under Ten Fishermens Association (NUTFA) to create a vehicle for the small-scale boats to be represented at policy level, with the main objective being to provide its members with the same rights and responsibilities enjoyed by the larger industrial sector. In addition to the unequal allocation of quota between large and small vessels, perhaps the best example of the current unfairness is that the larger vessels can retrospectively lease the necessary quota to cover any overfishing, but this is not an option for the under 10 metre boats. If you can imagine being out at sea, and catching a bumper net of pollack, a reasonable fisher would seek to land this fish rather than throw it back, dead into the sea (we did all vote for a ban on discarding fish after all) and if the system was fair then he could have done so without penalty. But as things stand, the small boats are fined while the larger vessels can take the whole year to legally book their catch.

The small-scale sector also suffers from catching species that are often ‘red rated’ by excellent organisations like the Marine Conservation Society, simply because there is insufficient scientific data on their local fish stocks or local habitat. Species are automatically red rated in the absence of robust data, making the economic viability of these fishers’ days out even less certain.

Current fisheries management from a conservation point of view appears broken. According to the Marine Management Organisation, UK landings were 1.2 million tonnes in 1913. Landings fluctuated between 0.9 and 1.1 million tonnes until the early 1960s, when they declined to below 0.8 million tonnes. They subsequently increased to peak at 1.0 million tonnes in 1973 (the year the UK joined the EU). Since then, landings have been in steady decline, stabilizing, since 2009, at around 0.4 million tonnes – the lowest levels of any year outside those of the two World Wars. In relation to landings, it is relevant to note that the efficiency of the fleet has improved beyond recognition in the years since 1913, yet catches have declined dramatically over that period – we are apparently using 17 times the effort to catch a similar amount of fish than in 1913, despite the massive improvements in fishing efficiency.

Article 25 of the draft Fisheries Bill currently going through Parliament, which seeks to emulate Article 17 of the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy, has been supported by a number of MPs seeking to move from the current quota system to one based on social, economic and environmental criteria as the basis for a greater share of quota. Access to fishing would be shifted towards those fishers able to demonstrate a wider benefit to the local community and with a lower environmental impact. A gradual move to a revised quota system, especially if it could be underpinned by additional quota as a result of Brexit negotiations (allowing UK boats an automatic right to quota caught within 12 miles of the UK shoreline), would make everyone a winner, rather than maintain the current situation of haves and have nots.

In spite of the mainstay fishing industry supporting Brexit, not all UK fishers are so keen on the departure from the EU. To some extent the Southwest fishers have already benefitted from the collapse of sterling and the subsequent increase in demand from Europe. With China’s middle classes growing at a pace, if Brexit leads to hold-ups on the EU border, it won’t take long for our fish to find a market in the Middle and Far East. Indeed, we’ve already started to see it happening with our shellfish. Might Britain become a country unable to afford the wonderful produce from our own seas?

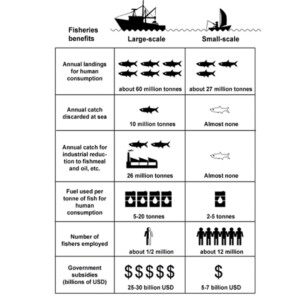

Comparison between large-scale and small-scale fisheries

The chart shows that small-scale fishing employs ten times as many people, has a much lower environmental impact, uses much less fuel and produces a fraction of the CO2 emissions, compared with industrial fishing – yet industrial fishing attracts far more subsidies than small-scale fishing.

To read more about UK fisheries policy, click here.

Photograph: David Smith