As a symbol of birth and renewal, eggs have long been associated with Easter and the arrival of Spring. This year, for less celebratory reasons, issues with eggs and, more broadly, with chickens are at the forefront of many a mind.

For starters, there’s been a crisis in the supply of eggs, a storm that’s been brewing for some time, driven by a confluence of ills: the continuing impact of bird flu, the inevitably increasing price of wheat – a staple in chicken feed – and the reluctance of retailers to pay farmers more, as their costs climb ever higher.

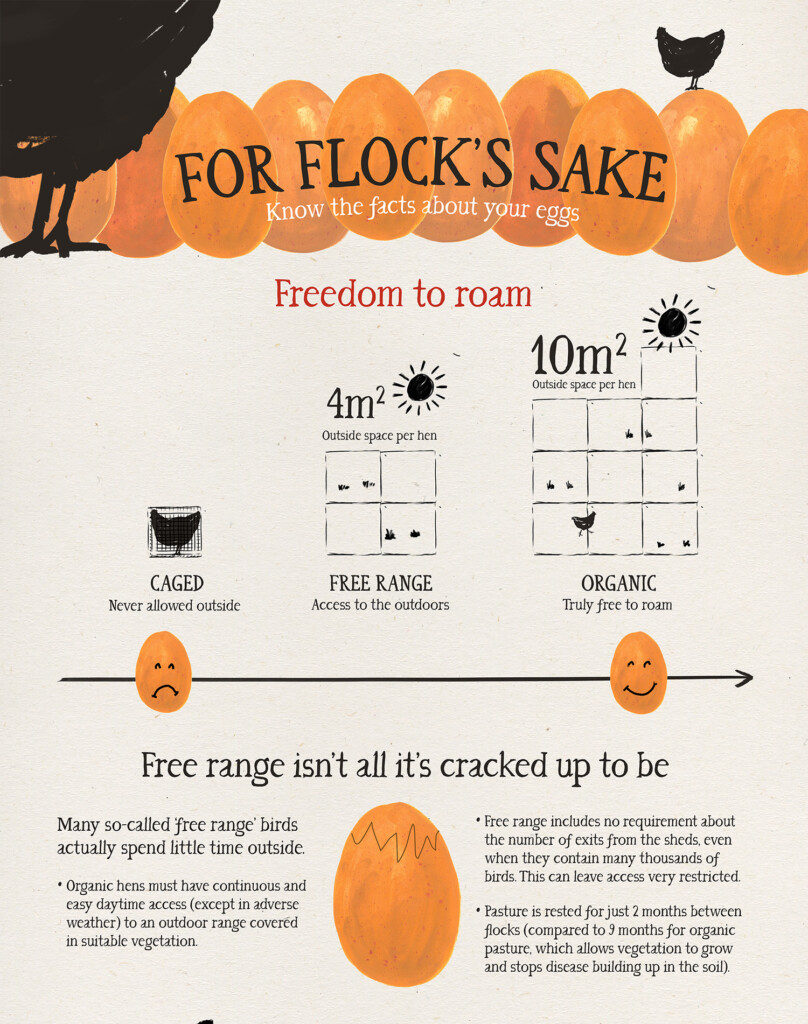

Sadly, bird flu has meant the return of housed chickens, likely to continue in winter months for some years. This year, starting in November, any flock of 50 or more chickens, organic or otherwise, were kept indoors. However, while this was necessary, it’s important to realise that most ‘free range’ chickens – which are most chickens – don’t get a lot of time outside anyway. The sole exception is for chickens raised to certified organic standards.

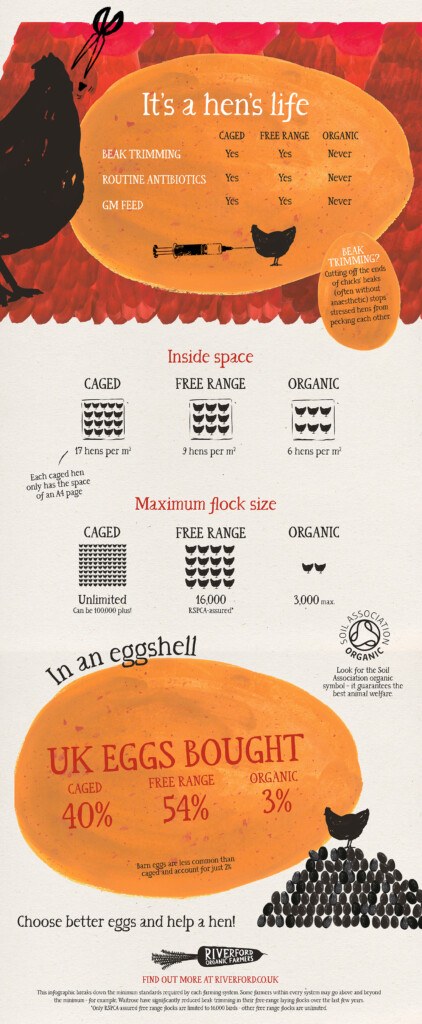

This tends to come as a surprise to many people. ‘Free range’ was supposed to mean just that – that chickens could range in pastures, enjoying the great outdoors. However, chicken accommodation varies widely as does the ‘enrichment’ element – and while there is a Code of Practice for pullets and laying hens, it is not a requirement by law. Many chickens are actively afraid of more dominant ones and this can deter them from accessing the ‘popholes’ which offer exit to the outdoors, with the number of popholes varying widely, from ample to minimal. And we should also remember that the ‘pecking order’ can be brutal, so in most free range flocks, beak trimming is a given, which is distressing to chickens, as one could imagine. It’s not their ‘best life’ – given the beautiful nutritious eggs and meat they produce for human consumption, they really deserve better.

Sixty years ago, eating chicken was a luxury of Sunday lunch and not a staple, but over the decades, as chicken was increasingly industrialised, the life of a chicken has shortened significantly (8 weeks is the norm for a conventional free range broiler) and on the caged (which still makes up 35% of chickens), barn raised and free range end of production, there is still much more that could be done to improve their lives. Conventional broiler chickens are genetically bred to grow at a rate much faster than their bodies can really manage, and the quick weight gain can leave them lame and subject to heart attacks. Slower growing breeds are better in terms of animal welfare.

Brits currently eat just over a billion chickens a year, and with the ubiquity of chicken, its value has fallen along with its welfare. Chicken is remarkably cheap and though there are many people who genuinely can’t afford to eat higher welfare chickens, there are many more that can. So, if you can reach a little deeper into your wallet, you’ll be doing a very good thing.

Just 3% of chickens are raised to certified organic standards. Comparatively, they are the lucky ones whose lives are most closely aligned with their needs and predilections. Organic layers and broiler chickens also aren’t given prophylactic antibiotics and GM feed. Flocks are capped out at 3,000 birds and it is good practice to divide large flocks into smaller groups. The RSPCA suggests 16,000 birds as a maximum flock size for free range, and caged and barn raised can be as many as 100,000 – have a think about the life of chicken in a flock of that many birds.

Perhaps it’s time to think differently about chickens and all that they provide for us and treat them better? Step up to organic standards – it’s often the same or even sometimes cheaper than free range and the difference to their welfare is actually immense.

The ‘Feeding Britain from the Ground Up’ report recommends a 74% and 48% reduction in our consumption of chicken and eggs respectively. Find out why and read more about the report’s recommendations here.

Infographic courtesy of Riverford Organic Farmers.