A partnership between Sara Grady and Alice V Robinson, under the name Grady + Robinson, will produce the UK’s first supply of leather traceable to British pastured livestock farms. The result will provide a unique opportunity for brands and designers to align their values with ecological and humane farming. A grant from the Prince’s Countryside Fund is supporting their pilot in partnership with the Pasture-Fed Livestock Association.

“What a pity.” “It’s depressing.” “A damn shame.”

It’s a refrain uttered by many livestock farmers who prioritise ecological and humane practices in their husbandry. What are they lamenting? The lack of value in their animal’s hide and the inability to control what happens to the hide once the animal is slaughtered.

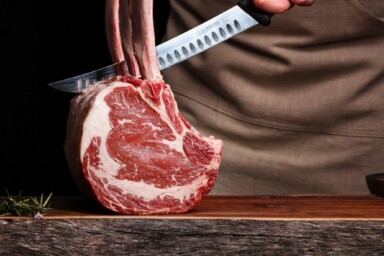

The hide is a significant part of what is yielded from an animal. Considering how much care and how many resources these farmers invest in their animals, it’s no surprise they want to see such a valuable part of their herd being meaningfully used.

‘We put a huge amount of effort in raising our cattle and are totally involved in the whole process: breeding, birth, growing, slaughter, butchery and marketing. We’ve done a lot to sell all the parts – meat, bones, offal – but at the moment, despite trying, it’s virtually impossible for a farmer to get their hide to a customer who wants that leather with a provenance,’ says farmer Andy Rumming, whose beef farm in North Wiltshire is certified by the Pasture for Life label.

Most often, farmers must accept that hides will disappear into an anonymous commodity supply chain, or worse, be discarded altogether.

Salted hides

Customarily, hides are sold by an abattoir to a merchant who deals in hides and skins (once called a ‘fellmonger’), then sold on to tanneries to become leather. Until several years ago, hides were valuable enough to bring smaller abattoirs a vital supplemental income in what is a narrow-margin business. Such revenue can be significant in stabilising the viability of local abattoirs (an issue of critical importance, with a third of the UK’s small red meat abattoirs having closed in the last decade, as documented by the Sustainable Food Trust) and helps to maintain the affordability of processing costs paid by farmers.

But in recent years, globalised trade and shifts in the supply chain have resulted in a loss of value for hides. Statistics sent from Leather UK, the trade association for the UK leather industry, show that between 2015 and 2020, the price paid to an abattoir for a raw hide dropped from £60 to £16 – a decrease of 73% over five years. This has been attributed in part to a rise in cheap synthetic materials and leather-like alternatives, in combination with a glut of hides resulting from a growing global appetite for cheap meat, as well as the vagaries of farming. The causes may be complex, but what’s become apparent is that the economic burden of worthless hides is borne primarily by small-scale farmers who may incur higher processing costs, and local abattoirs who must pay for disposal.

The ‘fifth quarter’ encompasses all the bits beyond flesh, including hide, blood, bones, organs and fat. The hide can represent as much as half the value of those by-products. But the desire for hides to be meaningfully used is more than economic. Most smaller-scale farmers say that there is value in the satisfaction of just knowing a hide will be used and enjoyed.

‘I hate to think that such a great potential product is binned or lost to the commodity market – we owe it to the animal to make the very best of every bit,’ says Rumming.

Meanwhile, customers and leather goods designers are seeking ethical and regenerative materials. It’s part of an awakening that echoes our food culture’s growing discernment for good meat. Eaters increasingly expect to have options at the butcher counter to be able to avoid meat from industrial systems (those that are destructive, polluting and inhumane), and instead choose meat that was raised with care. When animals are raised as nature intended – in biodiverse farming systems that emphasise animal welfare, soil health and ecology – the benefits are numerous, including environmental resilience, carbon sequestration, land stewardship and human health.

It won’t be a straightforward journey. Leather production has been increasingly offshored, resulting in few remaining tanneries in Britain. Today, the Leather UK website lists a total of 23 tanneries, only two of which tan bovine hides using traditional vegetable tanning methods that employ natural processes. Existing systems for collecting hides are geared towards large-scale globalised leather production, which means they are not well-suited to smaller-scale supply from local farms and abattoirs. And in the established leather industry, traceability does not yet exist from farm to finished leather. It’s impossible to know the source of a hide and the life that was led by that animal. Those wishing to choose leather according to values of animal welfare will be disappointed; there is no existing supply of leather that preferences sustainable farming practices.

This, therefore, is our starting point: we are currently sourcing hides from farms that are certified organic and/or 100% pasture-fed under the Pasture for Life label. We are testing new systems for collecting hides while maintaining traceability. By working with one of the last traditional vegetable tanneries in the UK, we will produce high quality, versatile leather suitable for various applications in both fashion and interior design. Our project will bring revenue and recognition to the participating abattoirs and farms.

The leather we produce will be a welcome new choice for designers and brands who embrace best practices of sustainability and ethical production. Success in our venture will depend on their support, and we will be working to cultivate an understanding of leather as an agricultural product. Our British grown-and-made leather will have a beautiful natural grain and patina that tell a story of how the animal lived. But it will also have more ‘character’ and less standardisation than mainstream leather, consistent with the natural processes inherent in its production.

We look forward to this challenge: it is an opportunity to engage new audiences and expand an awareness of practices that improve the welfare of animals, ecosystems and communities. The benefits of regenerative systems go well beyond good meat.

Featured image: Alice V Robinson’s collection titled 374, was created in 2019 entirely from one bullock. The piece was a part of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition, FOOD: Bigger than the Plate