Every year, 4.5 million tonnes of UK grown fresh fruit and vegetables are lost to aesthetic grading. Selecting produce for retail, based on its appearance, means that up to 50% of carrots produced will never reach a shop. These twisted, misshapen vegetables contrast starkly with the technicolour perfection found on Instagram, giving consumers conflicting messages. Why does our beloved carrot suffer so much?

Carrots are ambitious vegetables. From the moment a tiny carrot seed is scattered on the ground and watered in, it burrows down through the soil with single-minded intent, battling obstacles and disease on its way. After several months of growing, the plucky root is hoisted from its subterranean home, proudly revealing battle-scars it endured during its development. These imperfections tell the story of how this supermarket staple bravely fought with nature to grow into a proud, nutritious vegetable beloved of the British public.

The impact of aesthetic grading on fruit and vegetables

While perfectly conical, straight-sided darts of orange perfection are welcomed with open arms, other less fortunate carrots become victims of the grading process. EU regulations detail cosmetic standards and supermarkets impose their own, higher specifications on top of those. Grading sorts fresh fruit and vegetables according to size, shape and cosmetic appearance, and only the finest carrots hit the shop shelves, whilst those which display significant imperfections are set aside.

New research from the University of Edinburgh has estimated, for the first time, the quantity of losses in UK fresh fruit and vegetable production. Results show that up to 4.5 million tonnes per year are lost for cosmetic reasons, approximately one-third of all farm production. Carrots face the highest losses of all vegetables, approximately 24-50% are discarded due to cosmetic standards.

Throughout the food chain, people are working to increase the quantity of carrots reaching our stomachs. Dr Charlotte Allender is assistant professor at University of Warwick and loves researching these plucky roots. I asked if the battle against food waste starts before the farm? “Breeders work hard to produce new varieties for their customers, to provide solutions to the problems they face.” Important characteristics for farmers include maximising yields and ensuring robustness (the ability of crops to grow in challenging environmental conditions).

Developing new varieties has the potential to increase the quantity of cosmetically accepted carrots; Charlotte says “breeders are always looking to release varieties of roots with smooth skin and uniform appearance”. Breeding and selecting appropriate varieties of carrots is vital in reducing the percentage of cosmetically graded losses. “Growers wish to maximise their return, and minimising grade-outs is one way of doing this,” she comments. Long before a seed is sown, work to reduce losses from grade-outs has begun.

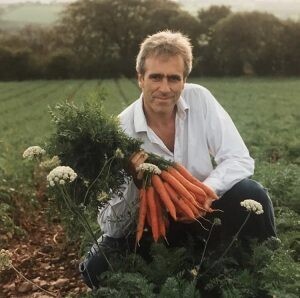

Farmers select seeds and adapt their production techniques to get the highest yield of carrots which make the grade. Patrick Holden, founder of the Sustainable Food Trust and a dairy farmer, grew carrots on his land for 27 years. He suffered up to 50% grade-out losses at the hands of supermarket standards. Patrick comments that, “Customers are hard-wired to choose cosmetically perfect produce, so you’ve got to have some sympathy with the retailers’ heavy grading. We buy on appearance, but if you knew the story behind the carrots then you probably wouldn’t want to buy them. When it comes to carrots, there is very little value put on flavour and nutrition. What’s produced instead tends to be tasteless carrots, often with chemical residues, that look cosmetically great.”

Patrick during his carrot-growing days

Patrick recognises that if a supermarket places a pallet of carrots in the veg aisle, at the end of the day, only the wonky broken ones are likely to be left. For this reason, he believes “unless consumers are given a strong motive to change this behavior, it will be reinforced.” Customers prefer good looking produce and let’s face it, straight carrots are easier to peel. Such were Patrick’s losses, that he began selling the misshapen carrots locally, packaged with a story to explain their appearance, and with his contact details on the back. It received a lot of positive feedback, showing how people need information to inform their choices.

Sadly, the closure of the local packhouse left him with no choice but to transport his carrots all the way from West Wales to Peterborough (the home of Sainsbury’s central packhouse). Ultimately, it forced him to give up selling carrots – highlighting the impact of a centralised, homogenised food system on the survival of local producers.

Some carrots, however, never even leave the farm, occasionally being ploughed back into the field. The high percentage of losses associated with carrots means they have one of the highest embedded CO2 emissions of any UK crop. Blaming the producer is futile, as farmers play piggy-in-the-middle. Patrick commented that “farmers are commodity slaves – they are anonymous and farm at the mercy of their customers”.

Supermarket practices could make significant impact

Supermarkets may enforce higher cosmetic standards to satisfy their own customers, however, change is occurring. Asda recently increased the percentage of carrots with cosmetic defects in their Grower’s Selection range from 10% to 40%. Produce technical director at Asda, Ian Harrison, says “It’s made a big difference to our suppliers – they can now sell more of their produce to us rather than having to go out and find soup factories or ready meals to put their less-than-perfect crop into,” showing some empathy for the farmer’s plight.

Morrisons are also making significant changes and have vowed to increase the number of farms from whom they buy the ‘whole crop’ to nearly 300 by 2019. This process sees the supermarket buying all the grower’s produce, regardless of size and shape. However, even as stores loosen their requirements and allow more veg through, there still remains a tranche of carrots deemed too obscene for consumers’ eyes.

Jenny Costa at Rubies in the Rubble saw a solution. “We started from a want to celebrate produce of all shapes and sizes and ensure no good food in the supply chain goes to waste.” Making award-winning relishes and sauces from waste fruit and veg was her vision, starting with family recipes cooked up at home. They are now stocked in supermarkets across the UK. Jenny says her idea “naturally preserves rejected fruit and veg (for size, shape or colour) in seasonal abundance, to be enjoyed throughout the year”.

Food waste campaigners WRAP boldly fight to reduce food waste. In July 2018, they released new guidelines for fresh fruit and veg grading, aimed at minimising waste. Yet, WRAP earnestly concede that imperfect food is “costly to supply” as it adds an additional channel into the supply chain which previously didn’t exist. Ultimately, the amount of misshapen carrots for sale in shops is dependent on “customers’ willingness to buy it”. Are carrots suffering at the hands of consumer vanity, if supermarkets are only providing food that people willingly take to the checkout?

The Instagram effect

Searching for #carrots on Instagram reveals a cornucopia of supermodel roots, while rejected carrots from Patrick’s field looked like they were born of Picasso’s surreal period. I recently researched Instagram food images at City, University of London, finding that humans are inevitably drawn to fantasy and perfection. While people may complain that Instagram isn’t real, these images of perfection fill the gaps in our everyday life, and it’s inevitable that they influence our choices. UK food culture is typified by spending increased time looking at food imagery online and in books, while time in the kitchen is decreasing. Any efforts to get imperfect veg in our baskets, opposes a modern culture which desires ever more colourful and hyperreal images than ever before.

A carrot is a carrot, regardless of shape or how many legs it has. This story is about people and the judgements we make, because everyone, at all stages of production, wants to sell as many carrots as possible. Consumer choice decrees that a twisted carrot gets ploughed back into the field or makes dog food at best. We need people who do not discriminate, who can accept that a carrot, whatever its shape, is as good as the next. Luckily, the UK food system is full of amazing people who support carrots every step of the way. This is one battle which the brave carrot will not fight alone.