Stand in the fresh produce section of any US supermarket and chances are that at least a third of the available fruit and vegetables on offer will have been grown in California. Half of all the state’s agricultural output comes from the San Joaquin Valley, the southern part of the Central Valley. With its dry, hot climate and extremely fertile soils the San Joaquin Valley has perfect growing conditions – provided enough water is available.

Large-scale agriculture in the southern Central Valley began in the early 20th century when one by one the rivers flowing from the Sierra Nevada Mountains were dammed. Most of the winter rain falls as snow in these mountains, and as it melts in spring, the water is caught in reservoirs behind the dams and can be slowly released during the summer months. This water feeds the fields in the Central Valley but also the ever-growing population of cities like Los Angeles, San Diego and more recently, Silicon Valley.

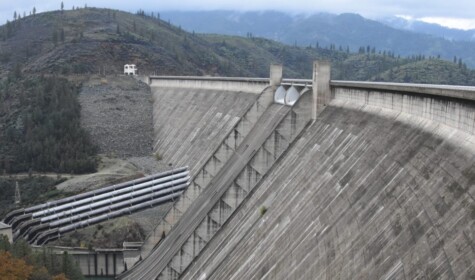

The other vital part of the California water system is the large-scale water transfer from northern California, rich in rain, to southern counties. The Shasta Dam near the border of Oregon, one of the largest in the US, holds back the water of the Sacramento River. Some 300 km south, the Sacramento meets the San Joaquin River and forms the vast California Delta, draining finally into San Francisco Bay. Huge pumping stations, on the southern side of the Delta, lift water more than 70 metres up again to the floor of the San Joaquin Valley and into a canal system that distributes it to farms and cities further south.

This vast water supply infrastructure is governed by water authorities and is heavily legislated. In an average or wet year, farmers in the San Joaquin Valley get a water allocation – which means they can buy a certain amount of water for irrigation. Water allocations for farmers have to be balanced with demand from urban areas, and the necessity of maintaining the Delta’s fresh and saltwater mixing zones. But when a drought hits, as between 2011 – 2017, the allocation goes to zero.

When I visited the San Joaquin Valley in late autumn of 2016, the situation for many farmers was desperate. Worst hit were the growers on the west side of the Valley, where the soil is extremely fertile, but farmers cannot drill wells because the groundwater is saline.

“Food grows where water flows”, reads huge billboards along the I5 motorway which runs through the Central Valley. Sitting in Joe Del Bosque’s farm office, you can hear the hum of traffic on the interstate. On a third of his 800-hectare farm, Del Bosque grows asparagus and melons, a third is an almond orchard, and in 2016, he had to fallow the rest. Water allocations are measured in acre-feet, one acre-foot equals roughly 1.2 million litres of water, and used to cost farmers about $130 per acre foot. Once the drought hit and the allocation went to zero, farmers like Del Bosque needed the local water board to negotiate water deals with rice farmers in northern California. Compared to almonds or melons, rice is a relatively low value crop, and for rice farmers it makes economic sense to fallow some of their agricultural land and sell the water rights instead. In 2016, farmers in the San Joaquin Valley paid between $1,000 and $1,300 per acre-foot to the water board. Some almond farmers, desperately fighting for the survival of their orchards, paid even more than this for their water.

From Del Bosque’s farm near Firebaugh, it’s about an hour’s drive straight east to Mas Masumoto’s peach farm near Fresno. Masumoto works with heritage peach and nectarine varieties and became one of the stars of the ‘farm to table’ movement, when Alice Waters, the founder of the renowned restaurant Chez Panisse in Berkeley, put his ‘Sun Crest’ peaches on the dessert menu: just one whole peach, no trimmings. The farm is certified organic and has two 50-metre-deep wells which currently still provide enough water to irrigate the orchard. Unlike most of his colleagues, Masumoto uses furrow irrigation. “Drip irrigation makes the trees lazy; the water is delivered directly to the roots. If a tree has to search for water, it develops a much deeper root system,” says Masumoto. In most orchards, the trees are taken out after about 15 years and replaced with new ones. On Masumoto’s farm most of the ‘Sun Crest’ peach trees were planted in 1968 and are still productive. Masumoto’s main worry is not the lack of water but the rising temperatures. If the winter months are not cool enough, the trees don’t go into dormancy and that “makes them cranky” says Masumoto – disease resistance and yields drop. He and his daughter Nikiko have diversified by planting the first olive and fig trees that, hopefully, will be able to deal with less water and more heat as the climate continues to change.

Conditions change again when you leave Fresno and drive another 50 km south until you reach Tulare. There’s lots of water available here – if you bore a well that reaches deep enough. “Tulare County leads the nation in dairy production,” noted the Farm Bureau in October 2018. Driving along country roads you start noticing the long rows of dairy sheds, open to both sides. In summer, the Holstein cows need between 140 and 200 litres of water per day and a misting system that keeps them cool. In the Tulare Basin, the aquifer is relatively accessible and when the drought hit, farmers didn’t have to rely on costly water transfers from the north, they just drilled new wells.

Kim Arthur runs Arthur & Orum Well Drilling, and since 2014, his order book is not just full, it has a waiting list. He remembers the time when a 100 metre well was considered deep. But as more and more new wells are drilled, they are drilling ever deeper to reach the retracting water table. To do so, Arthur bought equipment that is normally used by the oil industry; now his work crews can go down as deep as 1000 metres.

For a long time, farmers have pumped more water from the aquifer than could be replaced through rainfall. The drought made things a lot worse. A study published by the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) gives the figures: between 1988 and 2002, the water overdraft in the San Joaquin Valley was on average 1.3 million acre-feet per year; in the drought years between 2003 and 2017 the average went up to 2.4 million acre-feet per year. The consequences have been dramatic: many of the old wells, which were shallower, have fallen dry. That has left whole townships without drinking water – like East Porterville, 40 km southeast of Tulare, where citizens have had to rely on water deliveries by tanker lorries since 2014. Over 100 communities have contaminated tap water; in particular the shallower wells are contaminated by naturally occurring toxins like arsenic as well as agricultural run-off and wastewater dumps containing nitrate and solvents. The aquifer is being drained so fast that it has caused the land to subside; cracks are appearing in walls, roads and in many of the water canals. It became clear that things wouldn’t return to normal even after the end of the drought. Serious water saving measures had to be put into place.

In September 2014, then Governor of California, Jerry Brown, signed the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) into law which aims to end the water overdraft by 2040. The PPIC report calls the San Joaquin Valley “ground zero” for implementing the law. Despite the fact that the drought ended in 2017, the water overdraft for the Valley is at a staggering 1.8 million acre-feet per year. Switching to less thirsty crops, water recharge on farmland through flooding in winter, capturing more run-off and the expansion of the existing water trading schemes are listed as the best options. “This combined approach would decrease the need for land fallowing by more than a quarter, from 750,000acres [303,514.23 hectares] to 535,000 acres [216,506.82 hectares]… With this portfolio, GDP and job losses equal roughly 4% of today’s agricultural economy, and less than 1% of the total regional economy,” concludes the report. The upside is that not all the land will have to be taken out of production permanently; some of it can be fallowed as part of a rotation and installing solar panels may be an alternative way to derive income from fallowed land.

In 2014, California also introduced a ‘cap and trade’ auction of CO2 permits, and some of the proceeds go towards funding agriculture programmes. One of them is SWEEP, the State Water Efficiency and Enhancement Program. Farmers can apply for grants to finance measures that reduce the on-farm water and energy use. According to the website, more than $67 million have gone to over 600 projects – from soil moisture monitoring and drip systems, to more energy efficient pumps.

Farmers in the San Joaquin Valley have another 20 years until their ground water use must be sustainable. That may sound like a lot of time, but for some there will be no easy options to fix the problem – only hard choices. Water will become an even scarcer and therefore more expensive commodity. For farmers, it will only make sense to grow very high value crops like almonds, pistachios, peaches and nectarines, and in addition some annual crops like melons – in drought years these acres can easily be fallowed. For how much longer fruit and nut trees will be able to take the heat in a changing climate is another question.

Photograph: Marianne Landzettel.