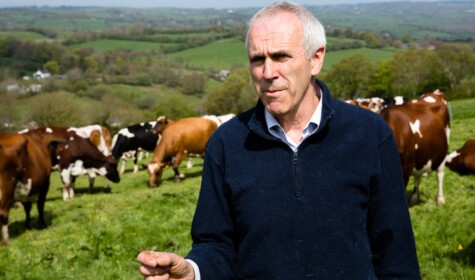

Here, we share a reflection from our CEO, Patrick Holden, who looks back at some of the SFT’s key moments from 2023 and explains why he thinks our voice is having impact like never before.

As we move through Advent towards Christmas, I want to start by expressing gratitude to our friends and supporters for your engagement with the Sustainable Food Trust. My heartfelt thanks for following us, if you do, and for your part in striving, as we all are, not only to make sense of the strange and challenging world in which we find ourselves, but also to ensure that in the future the food we eat has a better farming story behind it.

During 2023, the Sustainable Food Trust has been very much involved in the agricultural transition. While many are committed to making this a reality, there are still constraints that are preventing this from happening at the pace that is needed if we are to avoid irreversible breakdown in the Earth’s support systems.

We have been working top down, bottom up and in the middle, hopefully becoming an even greater influence for change than in previous years. Without over-claiming the progress we’ve made, I do think our voice is being heard in a way that wasn’t the case a few years ago. I shall do my best to illustrate this below.

COP28

Having recently returned from COP28, my lasting impression will be the incredible atmosphere of common humanity that arose from 90,000 people converging from across the globe, including so many young people, all of whom share concerns about whether we can keep the planet habitable for future generations.

At the summit, I had the opportunity to meet with the CEOs of some of the biggest banks, energy companies, asset management firms and supermarkets to explore how we can come together to support a sustainable farming transition. This was because nearly four years ago, the then Prince of Wales, now our King, launched the Sustainable Markets Initiative (SMI) at Davos, Switzerland. His idea was that, when it comes to reversing the destruction of nature and responding to the climate change crisis, we will only be able to do what’s necessary in the time available if we can harness the power of the business community to play their part in delivering the solution.

I can understand why some people feel sceptical about the private sector’s involvement in environmental and social issues given the tendency for companies’ claims about the sustainability of their products, services or operations to be seen as greenwash. Of course, we need such claims to be evidenced by trusted data if we are to avoid risk of greenwashing, but, in my view, the King is right when he says that we can’t ignore the power that private companies have and their resources to scale and accelerate positive change. Compare that with government actions as things currently stand, and one surely has to conclude that political parties generally follow rather than lead!

Through the SMI, 20 task forces have now been created – one for each sector, covering everything from agriculture to aviation, from banking to plastics and, well, you name it and it’s there. We are leading a task force focused on measuring land use sustainability impacts using the Global Farm Metric (GFM), which we explored in depth at COP28.