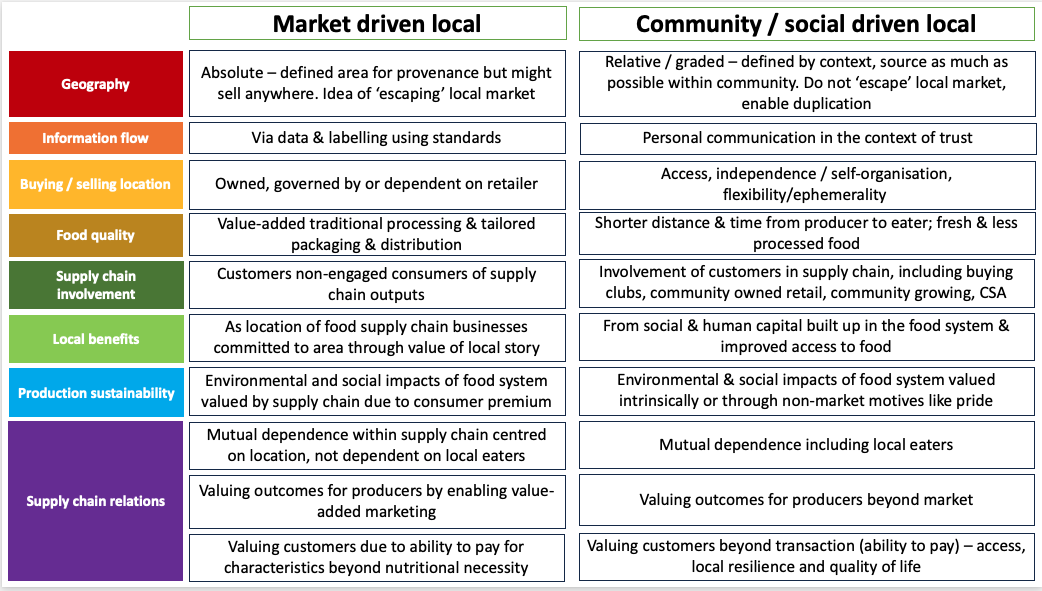

Let’s look in turn about how the aims of these two models of local food might be achieved and at some of the issues they raise.

Market-driven local

For producers, getting information about their product’s provenance, quality and sustainability to consumers, and shortening the supply chain – reducing the ‘middle-man’ between them and those consumers – are ways to gain better prices for their produce.

These approaches require farmers to have the resources and opportunities to either sell direct or to maintain direct traceability from their farm to the products the consumer buys. They require support for the sustaining of traditional practices and the required infrastructure for local production and innovation. But they also require that those who buy the produce, complete with a rich story about its qualities, value and provenance, can pay more for it than they would for similar products without such value attached. Indeed, producers may sell outside their local area to reach more affluent markets. As a result, the ‘food miles’ associated with products sold via this version of localness may be similar to products not sold as local. In essence, this form of local is, in many respects, compatible with the globalised food supply system.

Another vital aspect for ensuring fair rewards for farmers and growers is power and dependency in the food system. If a few large companies dominate a supply chain, it is likely that the added value generated by the solutions above will flow to those firms. This is because they can, for example, demand more from their suppliers at lower prices, being large enough to buy from elsewhere while their suppliers might struggle to find other outlets.

In the UK, food retail is dominated by a few very large firms which compete for market share. They do not necessarily make a large profit because their squeeze on the rest of the supply chain goes towards offering better deals to consumers, in order to keep their custom. If one company steps out of line and raises prices to give more to their suppliers, they are likely to be undercut by the others and lose customers. In these types of systems, there is little resilience to external shocks which increase the costs of production, like war or crop failure due to global warming – the already-squeezed supply chain is vulnerable to collapse, while consumers find prices rising beyond what they can pay. Neither of our core goals for local food are met and the situation encourages farming practices which are increasingly intensive and extractive, damaging nature and, ultimately, human well-being.

Community-driven local

So, we’ve seen what might need to happen to benefit farmers and growers in market-driven LFSs. We’ve also looked at why the current system benefits neither producers nor consumers. Now let’s turn to our community-driven local systems and how they might be supported.

For communities engaged in food systems, facilitating improved access to food for the poorest groups requires finding ways to source produce cheaply, from buying clubs where groups of people can gather together to buy in bulk, to food banks and surplus food hubs which take waste food from supermarkets and other suppliers.

These solutions include enabling people to grow their own food in community gardens, or to benefit from discounts on their food prices in return for payment in kind, for example by working on a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) farm. They are often driven by people’s desire to engage with and build their local communities, addressing isolation, sharing skills and knowledge and creating inclusive improvements in well-being.

However, if nothing else in the system changes, these solutions around access could mean that not only will farmers not be able to gain additional income from selling the ‘local’ story of their food, they may get less than they do now – because they would be supporting those who cannot afford to pay market prices.

Some solutions

Perhaps the greatest tension between the two LFS models we have described is the emphasis in one on rewards for producers and in the other on access to high quality food for the poorest people in society. In these models, the two aims pull the resources generated in the food system in opposite ways – can we imagine a system in which we pay producers better and support access to high quality food for everyone?

It is useful to think simply about what needs to happen to achieve this. For food to be more accessible and for its production to provide a proper livelihood for farmers, growers and food supply chain workers, one or more of the following things needs to be true:

- Less of the value created in the supply system is extracted by people other than eaters, farmers, growers and other supply chain workers.

- More value is created in the supply system.

- More value is added to the supply system (e.g., investment of money or of in-kind engagement, the provision of infrastructure and other resources).

- Eaters earn fairer rewards from their work, enabling them to pay more for food.

Here are some suggestions for how we might follow this logic to transform our food systems to meet the aims we have identified. They are gathered and developed from practice, work and thinking across food and farming systems and research:

- The implementation of a Universal Basic Income for farmers and other land workers, providing the financial stability they need to focus on product quality, resilience, environmental sustainability, social justice and the expression and development of their own values and farming ethos.

- Embedding the principle of food as a right in policy to ensure that access to high quality food for all is a pre-requisite for any food system.

- Pay-as-you-feel schemes focus on how food is valued, asking those with the means to contribute to our food supply to do so, proportionate to what they can afford. Payment in kind – via direct involvement in the food system – allows those with little money to enjoy good food as part of an exchange, rather than as charity. Arrangements for people who cannot afford to pay for food now, to agree to contribute to the system in the future, are another way to ensure dignity in accessing food – a concept reinforced by considering food as a right.

In many localised food systems, especially those involving small businesses, many decisions represent people going beyond the motive of profit maximisation to respond to social concerns and values. This embedding of human values in LFSs is underpinned by personal relationships between supply system firms and with customers, including informal peer-to-peer networks (like networks of farmers or the sharing of knowledge between retailers in different locations).

This value-driven model of food supply may incorporate ideas such as food as a right (highlighted above). In this way, while the actors in the food supply system make a fair living and invest in what they do, they are not seeking to maximise what they extract from the system, nor to dominate it – this creates the potential for both producers and customers to benefit. These values might be embedded via not-for-profits, community interest and similar innovative business models. They may arise through direct involvement in food supply by local communities, for example through community owned, cooperative and community interest independent retail. Human values can also be applied to develop fairer and more resilient food systems through initiatives encouraging profit-sharing and the management of risk to producers – for example in CSA schemes in which farms and eaters are connected, with the latter paying subscriptions in return for a share of the harvest.

Another way to bring human values into the food system and to reduce the extraction of profits is to move towards community, shared or public ownership of infrastructure, from land to data systems to equipment, from processing facilities to market halls. Such resources managed not-for-profit as commons, could be accessed by individual companies or skilled workers either for free or at cost price. Researchers like Elinor Ostrom have shown that the successful management of resources held in common is most likely in situations of interdependence and commitment – which we might expect in food systems where there is long-term engagement between small, local businesses.

In the UK, the Food Data Collaboration shows how collective ownership of data infrastructure can facilitate access to markets and improved fairness in distributing profits along the food supply chain, while building standards for the practices and product quality of businesses wishing to use these shared resources. The CSA network is another example of the value of collective ownership – a cooperative promoting, training and connecting CSA schemes. The concept of community restaurants, with local authorities supplying venues free or at reduced prices demonstrates how public ownership of infrastructure can grow food systems benefiting eaters and producers.

Again, drawing on Ostrom’s thinking, shared ownership of this type creates a way for people to gain a democratic say over the types of food infrastructure they want, how it is used and managed, and by whom. This involvement could present new opportunities for (and interest in) food systems, how they are working and what happens within them – reducing the disconnect between people and the production of their food. This opens space for conversations about sustainability and product quality, develops stronger and more stable relationships and (as a result) increases trust and the expression of human values in food systems.

As Ostrom discovered through her research, successful management of ‘common pool resources’ shared by all is likely to work particularly well where there is a clear definition of who is part of the community drawing on the resources, and who is outside it. This again highlights the importance of localised systems as a favourable environment through which these solutions could thrive.

Only allowing small businesses to access common infrastructure would increase the ability of such firms to withstand competition from corporates operating with economies of scale and able to cross-subsidise their individual outlets and facilities. This support for small businesses would increase food system diversity, enabling enterprises to join food markets without the entry barrier and ongoing burden of infrastructure costs, thus increasing innovation arising from healthy competition.

Local, shared facilities designed to handle small batches of diverse products would enable the products of small producers to enter the market without being lumped together, maintaining the link from the origin of products through to the final customer through which trust can develop. Common or shared ownership of infrastructure would also provide stability in localised systems, despite (due to small firm size) the likely churn of businesses entering and leaving the market.

At the ‘eating’ end of food supply systems, lack of access to good quality food needs to be tackled at root by a societal choice to reduce inequality and pull people out of poverty. This connects the issue of resilient, local, sustainable food systems to a much wider political debate. This connection is essential, otherwise our food system will continue to mask high levels of inequality by providing artificially cheap food – avoiding needed change and at a huge cost to the environment, communities and producers.

Tackling inequality goes alongside changing mindsets. While many people cannot afford to pay more for quality food (and often cannot afford to buy food at all), we need to normalise the idea that such food, sustainably produced, is valuable and requires supporting – either directly through prices or through public spending to drive the food system transformation discussed here. In turn, the solutions we’ve presented and their effects on how we all engage with our food systems can support that change of mindset.

Finally, to drive the change we need in our food systems, we must be able to monitor progress without constraining LFS diversity. This is important in keeping track of the use of shared resources and learning from change.

Monitoring should track progress in implementing solutions (e.g., proportion of small businesses in UK food supply systems, proportion of businesses with not-for-profit models) and how we are progressing towards desired outcomes (proportion of farmers/growers making a decent living through food production, percentage of people in food poverty, trends in diet and diet-related illness, average distance food products travel from field to fork). Monitoring should highlight effects on groups currently marginalised in society and within food systems.

But do we really need Local Food Systems?

Do the solutions we’ve looked at really require ‘localism’? The solutions above focus a lot on company size and supply system relationships – perhaps these, not locality, are most important for just and sustainable food systems? We could go further – the current globalised supply system can to some extent reproduce many of the potential benefits of local systems. Through the application of new technologies such as block-chain, more information about product qualities, backstories and production, can be shared with consumers without personal interactions; big retailers can and do donate to food hubs and community schemes, and can make money through stocking location-specific produce in local food aisles. Through government-driven regulation, the power of large companies can be focused to incentivise improvements in environmental sustainability and social justice along the supply chain. In these ways, it might be argued that we can gain many of the producer-side benefits of market-driven local food without changing much at all.

Here are some reasons why the ‘local’ needs to stay at the forefront of our food systems thinking:

Firstly, the well-being and dignity of farmers, growers and other agricultural workers requires them to have power to act as responsible professionals. This is essential for food production to be resilient and adaptable, drawing on producers’ rich, local expertise. Remote, top-down change – including incentives which farmers and growers have no control over – empowers centralised, abstract knowledge and ways of thinking. It degrades the capacity of farmers, growers and agricultural workers to develop leadership and innovation, takes both the responsibility for and satisfaction of achieving positive change away from them, and discourages new entrants to the sector at a time when the UK’s farming population is ageing.

From the perspective of human well-being and dignity, this is neither a healthy nor an efficient state-of-affairs and it can build resentment and increase the transaction costs of achieving sustainability gains.

The only solution to this issue is for food supply systems to become more co-dependent (rather than dependent on a few powerful firms) and more embedded in local communities, connecting them to social networks of support, to a deepening understanding of local issues and to a space for the expression of their own values. A LFS model in which those involved are motivated or forced to ‘escape’ their local markets is hollow and will, in the end, re-create the conditions and issues of the current system.

Secondly, the value of local systems is not just that they transfer information along the supply chain and support local initiatives – it is that they do so through the building of human relationships and networks of learning and experience. Both human and social capital are created in multiple ways and lead to conditions which spur innovation around how the supply system can work directly to improve human well-being and environment. Proximity is vital to these processes, and these processes are central to resilience. They create living engine rooms from which communities can evolve and innovate creative solutions to the challenges of public health, food security, global warming and the biodiversity crisis.

These arguments show why we should look to localism in food not only as a convenient shorthand for other things of value, but as something valuable in itself.

Resilience and networking the local

While localism creates more resilient communities closely connected to their food supply, it also brings a risk to resilience if problems like extreme weather events mean the local area does not produce the types and amounts of food needed. At the same time, solutions like pay-as-you-feel might create big challenges for areas with high poverty levels and few wealthy people.

These challenges highlight the need for governance structures across LFSs. These would aim to develop ways to support food infrastructure where people can’t afford to pay as much for products, drawing on funds from places where people can afford more, and to facilitate the trade of food between communities in which there are surpluses to those facing shortages.

We might imagine this ‘networked local’ model within the UK and beyond – recognising that while seasonality in diet should be maximised to reduce food system impacts, nutritional needs and multi-cultural populations require some trade in food between nations.

Clearly, such networking would need to avoid morphing back into the current global system. ‘Networked local’ should be –

- centred on fairness, dignity and rights, not profit maximisation and market share;

- based on interdependence and commitment, not domination and extraction;

- focused on connecting people and communities not just products through the nested governance of their food supply system.

Concepts such as food zoning, where communities try to source as much as possible from each successive zones, moving away from the centre of their area, can help keep a local focus, while communal governance and data sharing could connect local markets to each other.

Final thoughts

As we said at the start, LFSs are not guaranteed to be better than any other system in relation to environmental or social outcomes – but they offer the best chance for the development of solutions tailored and adaptable to changing local contexts. They enable processes of change which create value and well-being through the very act of attempting to tackle the issues together.

We believe that there is a route through the ideas shared here – but developed over many years by the broad and diverse local food movement and those working in it – to create food systems that provide good livings for farmers, growers, agricultural and supply chain workers, while delivering access to good quality food for all and engaging sustainably with nature.

Our full report will be released in the next few weeks. In the meantime, you can read more online about the Local Food Plan and – if you aren’t already – see how you might get involved in or map and create local food and growing initiatives in your area.