We share some initial thoughts on the Government’s food strategy.

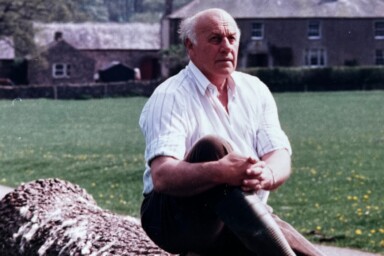

Patrick Holden, Sustainable Food Trust CEO, said: “This mix of half measures and future promises misses a huge opportunity to transform the way we grow and eat food. The strategy creates a false choice between food security and the environment. There is a win-win with the right mix of policies and incentives. An ambitious Food Strategy could build national food security, fight climate change, protect nature and improve our health, if it incentivises a different type of sustainable farming – one that is in harmony with nature, reducing the reliance on volatile food imports and Russian fertiliser.”

On farming and nature

While the food strategy does acknowledge that regenerative farming can have an important role to play, the overall trajectory of the strategy is towards intensification of food production, increased reliance on technological innovation and gene editing as well as a big emphasis on global trade. Our new report, Feeding Britain from the Ground Up, suggests a radically different approach, arguing that we should farm in harmony with nature, reducing chemical inputs by returning to mixed farming across the country. The strategy and wider government policy has seemingly abandoned its more ambitious proposals for nature restoration as the Ukraine crisis has pushed the need for food security front and centre. But it is a false choice between food security and environmental protection, and even between farming and rewilding. There is a win-win if done in the right way.

On metrics

It is good to see the need for a Food Data Transparency Partnership included in the strategy, based on consistent and defined metrics . These metrics must empower farmers to drive change. They must also extend beyond health and animal welfare and take a holistic approach to include all aspects of farming and food sustainability. The same is true for eco-labelling. These should not focus on single issues (such as carbon) and must be underpinned by common metrics agreed by the whole sector. It is imperative we give citizens an honest and full picture so that they can make informed food choices.

On local food and supply chain infrastructure

It was good to see proposals for public sector food to be procured from local, sustainable sources. However, there was no mention of the short supply chain infrastructure needed to enable this. The decline of small abattoirs, for example, is threatening the supply of local, traceable meat. In order to support a vibrant, sustainable and local food system, the Government urgently needs to invest in short supply chain infrastructure and address disproportionate or unhelpful regulation. Furthermore, local, sustainably produced food should be made accessible to all, and while it’s a great starting point, the Government should not focus solely on public sector procurement but should support citizens to buy locally through investment in diverse, local businesses, infrastructure and retail.

On school food and food education

While we welcome calls for a ‘school food revolution’, Defra needs to be more specific in promoting fresh, locally sourced, seasonal produce with school menus that reflect that. In many parts of the country, there are opportunities to link farmers and fishers to their local school networks. This cuts out costs related to transportation and other ‘middle’ costs between the producers and the schools. Catering contracts will need greater flexibility to allow for this. A review of the policy and delivery for the School Fruit and Vegetable Scheme should consider how much of the scheme is procured from the UK as currently, the majority comes from overseas. There is potential to regionalise the scheme and connect producers more closely to their schools and even to offer visits to see where the fruit and veg is coming from and how it is grown. None of the fruit or veg comes from organic sources at present and it would be good to see how this could change and what incentives could enable this. We need a longer-term vision for greater fruit and vegetable production in the UK that the School Fruit and Vegetable Scheme is wholly aligned to, along with other school catering contracts.

Food should be seen as more than as just an area of learning within Design and Technology. There are many opportunities to teach food education in a cross-curricular way that goes well beyond Design Technology into Science, Maths, Geography, History, Art and PSHE (Personal, Social, Health Education). This holistic approach, which could link the story of our food and the systems that produce it with what constitutes a healthy diet, is surely the way forward. The reference to the ‘Invisibility of Nature’ in Henry Dimbleby’s report needs a higher profile in this learning too, as our natural world is in crisis right now and education must play a key role in its long-term recovery.

The £5 million allocated to deliver a school cooking revolution could go much further. Knowing six basic, healthy recipes by the end of secondary school is not enough. We are disappointed there is no proposal to expand Universal Infant Free School Meals – these should be expanded to the whole of primary education, as was originally proposed.