SFT policy director, Richard Young, reviews a new book, ‘Realising Health’ by the historian Philip Conford. Reflecting on his own health problems and those of the nation he argues that this book holds lessons for us all and should be required reading for all those who develop health policies today.

At the age of 70 I don’t enjoy (if that’s the right word) perfect health. In fact, I have a number of health issues that cause pain and discomfort and limit my abilities and treatment options. To use a motor car analogy, if you took me into the garage for an MOT, the mechanic would probably advise getting a new model, rather than trying to patch the old one up again!

While the miles I have on the clock have clearly allowed time for squeaks and rattles to turn into something more serious, where body parts have needed replacing, I’m not sure any of my conditions are specifically age-related. Some of them can be traced to my childhood and prevailing medical beliefs at the time, which can now be seen as mistaken, one to an accident that could have been prevented, others can be linked to medical mistakes and incompetence. However, some are clearly my own fault and if I’d known what I know now, I could have done a lot more to keep myself fit and well.

The Origins of the Peckham Experiment

But enough about me. How are you?

That’s a question often asked, and we generally reply to all but our family and close friends, “Fine thanks”, or “Very well thank you”, even if we have a leg that’s about to fall off. But whether you have a defined medical condition or no inkling of disease, do you actually feel ‘very well’? Are you firing on all cylinders? Are you at the peak of your physical and mental powers? Are you totally at one with your local environment, your family and your job (if you still have one)? If so well done, but you are probably amongst the minority.

Questions like those, along with the question of what is needed to create perfect health were very much in the minds of two medical doctors almost 100 years ago. In order to find answers Dr George Scott Williamson and Dr Innes Pearse (later Scott Williamson’s wife) set up a cross between a medical and a social experiment in Peckham, South London. They felt it was important to help people realise their full potential but could see that a significant proportion of the population had sub-optimal health, even where they had no recognised medical condition.

The story of their work, their successes and failures, has long been of interest to a few individuals. It’s of interest to the SFT because it gets to the heart of what we want to bring about: a healthy population eating healthy and nutritious food produced in harmony with a healthy planet. It has also started to attract wider interest, as a quick internet search reveals. It is the subject of Conford’s latest book, Realising Health: The Peckham Experiment, Its Descendants, and the Spirit of Hygiea which runs to almost 600 pages (with the indexes). This is a weighty and penetrating work which sets the project in its period and analyses the influences behind it, the influence it has had, why it eventually folded and why it is still relevant today. In a very different way it is also, for example, the subject of a project, The Peckham Experiment: A Centre for Self-Organisation by the Art Assassins. I found listening to the young people talking about their project to be highly inspiring. They’ve grasped its essence and importance and spoke about it with genuine feeling. That touched me and gave me a sense of optimism for the future.

But, as the most thorough and comprehensive historian of the UK’s organic food and farming movement, Conford is able to set the Peckham Experiment and the issues which lay behind it – the linking of human health to that of the environment, the soil and the food grown in it – in a far wider context. The first organic farmers and proprietors of shops selling wholefoods and organic produce in the UK, from the 1930s onwards were well aware of the Peckham Experiment and its significance, even if most of the farmers who have converted to organic methods since, (and that includes me), have known little or nothing about it. Conford points out that Scott Williamson was not just one of the founders of the Soil Association, he was one of three key driving forces behind its establishment in 1946. Everyone who is able to buy organic food today owes a small debt to him.

Defining health

Typically doctors then (as now) defined health in terms of the lack of disease. We have assumed that a doctor who cures patients of disease, returns them to health. But Scott Williamson and Pearse felt this was only part of the story. For them, health was something more than freedom from disease, and could be nurtured and encouraged. As such, they felt at least as much focus should be put on creating health, as treating disease.

They believed that health is a positive state of fully functioning harmony with the environment, where individuals realise their full physical and mental potential through advice and the creation of conditions conducive to maximum health. Many of the things they advocated, such as, healthy diets, fresh air, exercise and community based recreational activities, have progressively become more available and been incorporated into healthy living advice. But, while it is hard to explain the subtle difference, Scott Williamson and Pearse were not even advocates of preventative medicine. Instead of preventing disease, they felt health should be promoted and encouraged, because that would both prevent disease and help people to realise their full potential. Some people today, as then, may see that as too idealistic, yet the healthiest in society bear witness to its potential.

Though it’s not clear they saw it like this, they were, in effect, attempting to create a new medical discipline, the promotion of health, quite separate from the treatment of ill-health and the prevention of disease. They believed that by creating the right living conditions, food, exercise and spiritual enjoyment, health could be improved and then healthy families would have healthy children. Over time they saw this resulting in progressively healthy communities and a progressively healthy nation, where we would need to spend less and less on disease treatment, rather than more and more, as is the case today.

Before continuing with the Peckham story, let’s just look at a few statistics to see why their ideas may still be relevant to the problems faced by the NHS and society today, even to some extent, the problem of treating so many patients seriously affected by COVID-19.

Today’s less than healthy population

Except where separately referenced, the statistics cited in this section come from Chapter 3 of Public Health England’s ‘Health Profile for England 2018’.

Average life expectancy has continued to increase in England, albeit only very slightly in recent years, but healthy life expectancy is now still the same as it was in 2009-2011 at between 63-64 years. However, the total burden of ill-health (measured by the number of years lived in poor health) increased by 17% between 1990 and 2016.

On average, one in every seven of us feels anxious or depressed each day. If we include other common mental health disorders, almost one in five people aged 16 to 64 are not functioning as well as they could be. That’s a very high proportion of the people society depends on most to work and pay taxes. In 2019, 850,000 people were suffering from dementia (1 in every 14 people aged over 65). This is expected to grow to 1 million people by 2025 and 1,590,000 by 2040. While this is presented as a result of the ageing population and some people may be more genetically predisposed, there is no automatic reason why older people should develop dementia, if they have a healthy diet and lifestyle.

Smoking is linked to both lung cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Yet, despite the continuing steady decline in the number of people who smoke, there has been no further recent decline in CVD during the last decade, which suggests other factors are increasingly influential. In 2017, 14% of adults aged 16 and over reported having a medically diagnosed CVD, almost exactly the same as in 2011. Ironically, the Peckham doctors did not recommend giving up smoking, presumably because they were not aware at the time of the links with lung cancer, which were not established until the 1950s. Clear evidence of a link with CVD would not come till much later still.

Between 2 million (NHS stats) and 2.5 million (Macmillan Cancer Support) people are living with or after cancer and half of the entire population now develops cancer at some point in their life, 35% of people before the age of 65. According to Cancer Research UK, 38% of all cancers are preventable by changes to diet and lifestyle. Other diet and lifestyle-related diseases are also increasing rapidly. Almost four million people are affected by type-II diabetes and this is projected to rise to almost 5 million by 2035. Pre-COVID-19, the cost of diabetes treatment was already taking 10% of the entire NHS budget and this does not include the costs of medication and care in the community, which more than double this. Obesity too continues to increase. Between 2007 and 2017 the proportion of obese adults increased by 12% from 25% to 28% of the population. But according the UK Government, more than a third of all children in the UK are also now obese by year 6.

When it comes to COVID-19, what is abundantly clear is that those who are most overweight (and that includes me) are at the highest risk of serious complications and death if they become infected. It therefore follows that in general, those who have kept themselves fit, and are not overweight, are likely to get over the infection much more quickly.

Phase One of the Peckham Experiment –1926-1929

Between 1926 (the year my father was born) and 1929 just under 1,000 families were encouraged to join a club and paid one shilling a week (5p in today’s money, but equivalent to £3.58, based on inflation). This gave the whole family access to swimming, dancing, various games, including badminton, boxing, snooker and darts, as well and other activities, health advice and an annual medical check-up. The doctors did not undertake treatment for ill-health, they dispensed advice not drugs. When they detected health problems, they told the club member. However, they refrained from telling people what to do. They had an innate belief in people’s common sense. If and when a member decided to seek treatment, they would advise about their options and when necessary help to arrange an appointment.

Phase Two – 1935-1939

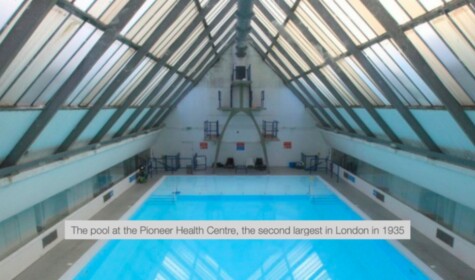

In 1935, after consideration of their initial research findings, funds were raised, all from private sources, to build a state-of-the-art medical and community centre, the Pioneer Health Centre (PHC), in Peckham. The swimming pool (see photograph at the top of this article) was the second largest in London at the time. The centre also included a large gymnasium, community hall, dance floor, games rooms, small cinema, cafeteria, consulting and changing rooms. With the cafeteria running parallel to the pool, people could eat, drink and relax while watch others swimming. There was even a roller skating and exercise park on the roof. The design was modern, light, open-plan and comfortable. It was open every day except Sunday from 2 pm until 10 pm and the members were encouraged to think of, and use it, as their centre, which it appears they did.

From 1935 Innes Pearse leased a farm at Bromley in Kent where organic food (not widely available at the time) was grown for members of the PHC. In 1950, after what was initially hoped would only be the centre’s temporary closure, the farm was taken over by Mary Langman. Mary had been Scott Williamson’s secretary and through him and Pearse she developed a deep and enduring interest in the holistic approach to health. With them, she was one of the founders of the Soil Association.

Then, during the 1960s with others, including Yehudi Menuhin, she established Wholefood of Baker Street, said to have been the first and most famous shop for whole and organic foods in London. With the combination of the practical experience of running a 125-acre organic farm and the intellectual understanding of the link between wholeness and health, she played a very important role in the early development of the Soil Association’s organic standards and through that, the wider availability of organic food today. Unlike some of her generation who believed the Soil Association should simply concern itself with research, she was forward-looking and recognised the critical role the organisation should play in bringing credibility to organic certification and ensuring it represented the core values of its founders.

The PHC building, which was of significant architectural interest, has since been converted to housing. A good impression of what it was like, however, can be gained from this slide show and this Central Office of Information film. Although the film seems incredibly dated with what must be a contrived (even if perhaps not atypical) family story, it provides a good picture of the centre and the doctors’ approach.

They found that approximately 30% of their members had clear evidence of disease, while only 10% were fully healthy. With the remaining 60% of members, while they could find no evidence of specific illnesses or disease, they could find no evidence of health either.

During this period, interest in public health was growing, including the extent to which housing, working conditions and other factors could affect human health. While the approach of the PHC was the most radical of its time, it was not the only one.

Phase Three – 1946-1950

During the war the building was commandeered for the war effort, and like many other London buildings so used, it was in a sorry state afterwards. Nevertheless, local people were so keen to see it reopened that a major voluntary effort made this possible very quickly.

Why the Centre closed

The centre finally closed in 1950 (the year I was born). After the war, the lead up to the creation of the National Health Service in 1948, over-shadowed the work of the PHC. In addition, the Peckham doctors, especially Scott Williamson, had very strong views and didn’t make themselves popular with the authorities by arguing that the NHS was not a health service, but a disease treatment service and refusing to conform to and be integrated into it, like other private centres, such as The Finsbury Health Centre.

Given what we know about the costs of running the NHS today (£140.4 billion in 2019-20) it’s not difficult to see why the centre, initially funded by a few individual donors and trusts, including the Rockefeller Foundation and by a subscription of one shilling a week per family, could not survive indefinitely without support from central government. They eventually doubled the subscription to two shillings and made repeated efforts to obtain government funding for the research side of their work. The PHC had some influential and enthusiastic supporters and for many years the Medical Research Council seemed to be on the point of providing funding, but it never came, not a single penny.

This august body, does not have an entirely blemish-free record of supporting important medical advances in their early stages. They happily list the development of penicillin on their website today as one of their successes, but omit to mention that when the Oxford scientists who developed penicillin first asked for £600 from the MRC in the early 1940s, they were given only £25 (equivalent to £1,400 in today’s money). A further small grant followed later, but this general lack of financial help was one of the factors which eventually forced them to seek support from the American Government and US companies like Pfizer and Lily, who then obtained international patents for the production of penicillin, forcing British companies to pay royalties to US companies for every unit of penicillin they later produced.

In one of the many brilliant and perceptive sections of the book, Conford analyses why the PHC was unable to secure MRC funding. He notes that Scott Williamson was closely associated with the first attempts to establish organic farming and that those who supported this approach were invariably also critics of the agrochemical industry. He doesn’t present evidence that Scott Williamson was blacklisted as a result, but he says,

‘The level of hostility to the chemical industry’s critics [i.e. the Soil Association and some organic farmers], demonstrated by the fertiliser companies and pharmaceutical firms, seems out of all proportion. Here we find ourselves facing one of the major factors working against positive health initiatives: the resistance posed by vested interests.’

He goes on to mention some of the authors who have since exposed the dirty tricks of ‘the powerful commercial combine’, but then explains the ingrained vested interests of medical professionals who (I add) through no fault of their own, were trained to adopt a certain view of the world. He notes that their education as health professionals ‘rewards them with a social status….which also benefits from the widespread confusion of medicine with health’. Our culture, he says, tends to value the work of those who cure the sick more highly than the work of those who help to prevent us becoming ill in the first place. He says, ‘Doctors are invested with almost heroic qualities. They are seen as scientists who can diagnose and healers who can provide relief or cure.’ While Conford recognises the brilliance of those who, for example, perform brain surgery, he wonders whether we have the balance of our priorities right.

This is a really interesting and difficult issue which lies at the heart of the problem and the heart of the book. There are exceptions, of course, but the wealthy in society generally have better health than the poor. They have better living conditions, better diets, better education and in general have the time and resources to look after their health better than the poorest in society. Efforts since the war, much of it due to the creation of the welfare state, have brought about some levelling up, yet, as the population has increased, aged, become more urban, and changed its diet, the statistics quoted above show that the levels of chronic ill-health in society threaten to overburden both the health and social care services, by taking an ever-increasing share of the budget.

The likely impact of this is illustrated by what is happening at present. COVID-19 is putting NHS staff under the most severe pressure they have faced since its creation. We know that many people affected by other diseases, especially cancer and CVD, are already dying because the NHS can no longer accommodate them due to the high number of coronavirus admissions, or because they are too frightened to seek treatment, in case they contract the virus. The BBC reports that this could result in between 7,000 and 35,000 extra deaths from cancer alone. This will have an impact far into the future, but it does at least give us a glimpse of what will happen anyway within a decade or so, if we do not improve the health of the nation as a whole and the NHS becomes overwhelmed by more mundane chronic diseases, as some have predicted. As such, we should see it as a warning which we need to heed.

Conford hints that maybe we have to put less resources into treatment, especially of rare conditions, in order to do this. This is where it gets very tricky. As someone whose life has been saved three times by brilliant surgeons, from conditions that in two cases were untreatable less than 20 years ago, and who would have died from blood poisoning at the age of 4, had it not been for the development of antibiotics just a few years earlier, I can see this from both sides! Clearly, I am hugely indebted to the skill, dedication and professionalism of my surgeons and see the word ‘heroes’ as fully justified in their case. Yet, while I can only guess how much my operations cost the NHS in total – well in excess of £50,000, I would estimate – I can now see that each of the operations could have been avoided for a fraction of that sum.

I won’t labour my own example any further, it’s illustrative but probably not that typical. Clearly the problem faced by society is how to get everyone to take their own health more seriously and how to put sufficient resources into medical training, so that doctors are better equipped to dispense more sound advice and less drugs. That’s a challenge in itself given that so many of us now depend on operations and other expensive treatments. Yet, sadly we haven’t even reached a stage yet where society or the Government realises that we need more than just a few posters about healthy eating to produce a healthy population.

Conclusion

With many of the PHC resources (pools, gyms, dance floors, community centres, skate parks) now more widely available, what would Scott Williamson and Pearse say is still missing, which accounts for our health problems today? Here I can only speculate. One of the most interesting aspects of the PHC approach is that they considered the family, rather than an individual as the basic unit of society. At the time, of course, most people lived in a family until they got married. The phase of converting large Victorian and Georgian town houses into flats had not yet arrived. But their view was that an individual could not be healthy unless the whole family was healthy. A second point which differs from today is that they felt that every family and member of it should have a health check-up once a year, even if they felt perfectly well. This allowed them to spot changes in health that might become significant and take appropriate action before it was too late.

It would have horrified them to see our reliance today on supermarkets and the highly processed and denatured foods, including most bread and foods with added sugar, which make most of their profits. The first UK supermarket opened in 1951, the year after the PHC closed, though I didn’t encounter one until the 1960s and that was little more than one of today’s late night shops in size. They would also, I’m sure, have pointed to the massive increase in the use of fertilisers and pesticides that has taken place in agriculture. They would have linked the pesticides with a number of health issues, as some academic papers do today (though without being able to quantify the impact), and they would have linked the phenomenal increase in the use of artificial fertilisers with declining levels of important trace elements in food, such as zinc and selenium and antioxidants like beta-carotene, all of which naturally help to protect us from disease. Despite eventually buying a chromatography machine, the Soil Association was never able to find conclusive evidence of such a link, but more recently scientists have started to find evidence to justify the instinctive beliefs of its founders, as this research paper from Newcastle University reveals.

Other aspects, I suspect they would have noted, are the almost total reliance of GPs today on prescription medicine and their lack of ability, confidence (or willingness) to provide advice and say, for example, let’s have a look at your diet and lifestyle. Then once that had been assessed say, if you change your diet (in this or that way), take more exercise and lose weight or whatever, I won’t need to put you on medication for life and that will be better for you in the long term and also help to keep down the cost of the NHS.

They would, I am sure, recognise the amazing achievements of the NHS and its dedicated and incredibly hard working staff, but they would also see our high and rising levels of certain preventable conditions (and therefore, reliance on treatment rather than health creation) as the central failing of a floundering approach to health.

Yet, it is not, of course, as simple as I’ve made it sound. Under the current system, even if doctors had all the wider skills, they do not have enough time to assess patients fully and dispense much advice. In addition, we may not want to hear it, or even if we accept it, we may not be able to follow it due to family, work, financial or other constraints on us. It does, though, seem to me that we have to start spotting emerging poor health sooner and start moving in the direction of cultivating health, especially in younger generations, rather than just treating it later. If we do not, it is difficult to see how the NHS will cope and how society as a whole will be able to pay for all the medical care that will be needed in future.

I’ve only been able to scratch the surface of this important book. It’s a book that raises issues all those involved in developing healthcare and public health policy should consider and also discuss more widely. We can’t go entirely back to the approach the PHC advocated and some of it was arguably flawed or too idealistic, but we could still take lessons from it. This could save us from the collapse of the NHS, as we know and love it, but of course there will always be those with vested interests, for whom a reduction in the number of drugs doctors prescribe is the last thing they will want to see.

Even after having read the book I don’t feel I fully know George Scott Williamson. He comes over as a very caring and strong-minded man, but I can’t be sure how much I trust all his ideas. In some ways his approach is Conservative, with its emphasis on the family unit and the creation of an environment where people are encouraged to be in charge of their own health; and in others it is quite left wing, with its holistic approach to public health, concern with working class living conditions and emphasis on community.

I put this aspect to Philip Conford and he replied, “The political point is apt. GSW’s book Physician, Heal Thyself (1945) outlines his objections to the proposed NHS, and sketches a sort of “Third Way” idea which he terms “liberal socialism”: rejection of both the capitalist ethic and the centralised State, preferring a communitarian view of society. He greatly disliked the idea of a doctor being subject to State control, and in fact had been opposed to Lloyd George’s insurance scheme, before the First World War. He apparently denied being an anarchist, but his ideas might well appeal in certain respects to right-wing libertarians, whose ideas seem to me to come close to anarchism – except an anarchism which favours the unrestrained power of corporations and Big Business, which is not what GSW would have wanted either.”

The story of how the book came to be written and who has taken the PHC approach forward since is extremely well summarised in Conford’s own Introduction which is available on the publisher’s website. Conford’s peer-reviewed paper, ‘Smashed by the National Health? A Closer Look at the Demise of the Pioneer health Centre, Peckham’, is also freely available online.

I am indebted to my colleague Robert Barbour for helpful comments and suggestions after reading a draft of this article.