Did you know 2016 was the UN International Year of Pulses? It would have been easy to miss it, as the humble pea, bean and lentil are at first perhaps not the most attention grabbing of foods. Pulses are a staple in many cuisines across the world and are a versatile form of nutrition, but how ‘sustainable’ are they? The Sustainable Food Trust is interested in the types of diets we should be eating to support a shift to local, sustainable agricultural systems – what role do pulses play in the UK context?

Pulses are edible seeds in the legume family. As crops, they are harvested only for their dry seed, which excludes green beans and green peas (because with these, you also eat the hull, as well as the seed). Pulses also exclude crops that are harvested for oil production, such as peanuts and soya beans. Horses and oxen were once fed large amounts of peas and beans as they were a key mode of transportation before the advent of the internal combustion engine. Today pulses grown in the UK are mainly used in livestock feed for meat and dairy animals, fish food, the food industry and for export.

Are pulses a thing of the past in UK diets? Beans and peas were at one time staple foods, especially as meat and dairy were largely unaffordable to most of the population. It was only in the early Middle Ages after the Black Death had dramatically reduced the population, that meat became more available for poorer classes. By the Victorian era, the wealthier classes ate meat on a daily basis, but low income families could only afford it 2 – 3 times per week or not at all. While it is difficult to estimate historical pulse consumption rates, Ken Albala who studied the history of beans found that, British cookery books indicate that by the 18th Century fava beans had been banished from elite cooking and stigmatised as ‘poor man’s meat’ and animal feed. Over the centuries traditional British bean dishes using fava beans were slowly replaced as New World bean species were increasingly imported and became more affordable. In the UK today, we eat fewer pulses than average around the world. Pulses are most commonly seen as a quick and cheap means of filling one’s belly, usually in the form of baked beans, arguably the UK’s national dish.

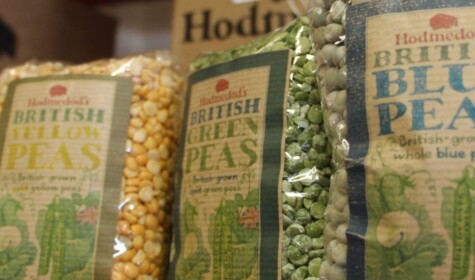

In the UK, 1.5 million cans of baked beans are purchased every day, and all the beans used in this product are imported. Baked beans are typically made with navy beans (Phaseolus Vulgaris), also known as haricot beans, which are not well-suited to the British climate, though could possibly be grown in the South of England. These are predominantly grown in the US and Canada. Britain grows about 400,000 tonnes of pulses a year, a high proportion of which are field beans (Vicia faba), also known as fava beans, and it is one of the biggest fava bean exporters globally, mainly exporting to Egypt and Japan. The UK’s other main pulse crops are marrowfat peas and large blue peas.

The greening regulations in the reformed 2015 Common Agricultural Policy have encouraged farmers to introduce pulses into their rotations, which is predicted to increase their production by 30%. This has the potential to bring many benefits. Considering that 70% of proteins fed to animals in the EU are imported and it is increasingly difficult to source GM-free varieties, there is a strong case for growing more home grown proteins in the UK for both human and animal consumption. Pulses are attractive to pollinating insects, add diversity to rotations, need little if any nitrogen fertilizer and can leave from 40 – 125 kg of nitrogen in the ground, reducing the amount that needs to be applied for the following crop. However, pulses are not easy to grow and many UK soils are not ideal for their cultivation. Controlling grass weeds is particularly difficult, especially on organic farms. Conventional growers use both pre- and post-emergence herbicides. Pulses cannot be grown in a rotation more frequently than one in every five years, because they are prone to a wide range of pests and diseases. They are also treated with insecticides and other pesticides (except on organic farms) which pose a threat to pollinating insects.

The International Year of Pulses has generated a lot of interest in the health benefits of eating pulses and the potential to increase production of beans and peas in the UK, as well as lesser known pulses such as lupins. Crop scientists, anti-meat campaigners and arable agribusiness have been quick to jump on the pulse bandwagon proclaiming their benefits, but the role of pulses in UK agriculture is perhaps limited, for the reasons detailed above, and still not entirely clear.

While there is plenty of room to include more pulses in UK diets as they are nutritionally beneficial and can help to rebalance diets high in carbohydrates and sugar, it is important to think carefully about the impact that this has on agriculture and food systems as a whole. Eating imported pulses produced in large-scale monocrops with significant chemical inputs will not help the shift to more sustainable farming systems. However, it may be possible to integrate small-scale pulse production on diversified farms in ways that increase soil fertility and provide local products for both human and animal consumption. Hodmedod’s is a unique British business pioneering the revival of local pulses. The Sustainable Food Trust went to visit Hodmedod’s lentil field trials and their warehouse to find out more about the potential of British-grown pulses and their role in sustainable farming.