When I was a child, my Dad and I had regular arguments about whose turn it was to have the ‘top of the milk’ – that thick yellow head of cream on the daily pint that we both coveted for our breakfast cereal. More often than not, someone would go out to the doorstep only to find that the blue tits had got there first, pecking through the foil lid to the sustaining food beneath.

‘Well it’s probably the same milk,’ Teresa Allward of Langford Farm informs me, before going on to explain that the cows they are milking now are the descendants of those that were supplying the milk for the local delivery rounds in the 1960s and 70s.

While this continuity of family and livestock is reassuring at a time of displacement and urbanisation for many rural communities, it doesn’t explain why this milk is so different in colour, texture and taste. In fact, it turns the question on its head. If this milk is so unchanged what has happened to the rest?

Homogenisation and intensification

The homogenisation of milk began at the turn of the 20th century when French inventor, Auguste Galin, patented a machine that broke down the fat, distributing it evenly throughout and preventing it rising to the top as cream, creating ‘a stable fat emulsion’, as one commentator appetisingly put it.

There appears to be no nutritional or health advantage to this process; appearance, shelf life and uniformity seem to be the main drivers for homogenisation.

‘White water, we call it,’ Teresa continues, disdainful of what passes for milk on many supermarket shelves that, not only has been homogenised, but also comes from increasingly intensively reared cows, bred for their high yields rather than taste or nutritional value. And, with some retailers charging as little as 48p per litre, this milk often costs less than bottled water.

Pasteurisation

When a person walks into a supermarket and buys a pint of milk, I doubt they give much thought to the processes that it has undergone before it is presented – pure, white and attractively packaged in its plastic or tetra-pack container on the refrigerator shelves. They may know that it will have been pasteurised and that pasteurisation will keep them safe from harmful bacteria that could potentially damage their health. What they may not consider is that if milk is heated to a temperature that kills dangerous micro-organisms it also kills beneficial ones that assist digestion and the development of a healthy immune system.

I am not suggesting that the pasteurisation of milk or other dairy products is a bad thing in itself and I have no doubt that it has saved many lives since its invention in 1862 by French microbiologist Louis Pasteur. However, along with the possible destruction of the potentially health-giving components of milk, there are other factors to consider.

The sale of raw unpasteurised milk is illegal in Scotland and restricted in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, with producers having to comply with increased hygiene and animal health standards as well as more frequent inspections. The mass production, mixing and transportation of milk would not be possible without pasteurisation because the exceptionally high standards could not be routinely met, breaches easily traced or longevity of the milk maintained.

While the ability to safely destroy pathogens in our food (without having to resort to such methods as washing it in chlorine) is desirable, there are inevitable downsides. One may be the loss of health-giving properties but I will leave that contentious issue to others to debate. However, there are other consequences of an increase in processing.

What is lost

The more processed milk becomes, the more reduced become the options for its use. Sour cream and crème fraiche, for instance, can only properly be made with raw milk. Commercially, pasteurised milk has lactic acid cultures and fermenting agents added, but at home it would spoil and become unsafe rather than souring in the traditional way.

Cream and butter cannot be produced at home from homogenised milk as the fat has been distributed evenly throughout and cannot be separated. As children, my sister and I would be given small jars of milk to shake so that we understood the simplicity of the process that turned milk into cream, butter and buttermilk. (If you want to keep your children occupied during lockdown give them a jar of homogenised milk to shake – they will still be shaking it at the beginning of December!)

Buttermilk was originally, as its name implies, the slightly acidic liquid left in the churn after the butter was extracted. It was considered to have almost magical properties, as Darina Allen describes in her book, Forgotten Skills of Cooking: ‘During turf cutting, haymaking and harvesting, buttermilk was considered to be the best drink to give energy, slake the thirst and cure a hangover. Young girls washed their face in it to improve their complexion, while their mothers and grandmothers used it to make bread.’ (Bread, of course, being another staple food that has often been processed beyond recognition.) These days the product labelled as ‘buttermilk’ is more often than not low-fat pasteurised and homogenised milk with lactic acid bacteria added.

The importance of diversity and the problem with a uniform food system

Charles de Gaulle once said, ‘Comment voulez-vous gouverner un pays qui a deux cent quarante-six varieties de fromage?’ – ‘How can you govern a country that has two hundred and forty-six varieties of cheese?’

There are many more varieties of cheese produced in France today than those referred to by its president half a century ago and more again in the UK. According to Peter’s Yard: A Guide to British Cheese Varieties, Britain currently has more than 750 cheeses. While large scale cheese producers use pasteurised milk that they then add bacterial cultures to, many of the smaller cheesemakers, of which both the UK and France are fortunately blessed, continue to make cheese in the traditional way. This involves using the natural micro-flora in raw milk to culture the cheese. The risks of harmful bacteria in unpasteurised cheese are lower than those associated with unpasteurised milk because cheesemaking is designed to take a product that spoils quickly (milk) and make it suitable for storing for a long time.

While pasteurisation is undoubtedly a great aide to preventing food poisoning it cannot be denied that, along with homogenisation, it also aides the mass production, centralisation and standardisation of our food. While marketing techniques of the large-scale producers and supermarkets constantly remind us that this is what the public wants, we ignore the implications at our peril.

If we expect food to have a uniform taste, texture and appearance we become unaware of that food’s provenance, its unique qualities, its regional and seasonal variations. Our palates become used to a narrowing of flavour and sensations, particularly if processed foods are relied upon as a mainstay from an early age. Anyone who has ever compared standard jars of baby food will know that it is difficult to tell them apart, with stewed apple tasting much the same as pureed carrot. A study carried out by Children of the 90s links this to the reduced consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables in older children.

When we lose the opportunity to purchase a product in its natural or near natural state, we lose confidence in our ability to process it ourselves and we lose our connection to the land from which it came. Small farmers and artisan producers struggle to compete with the reduced costs and long shelf life of factory produced foodstuffs. Ultimately the environment and animal welfare suffer because, while it is possible but not essential to produce food destined for the mass market well, it is not possible to produce and sell raw ingredients such as milk poorly.

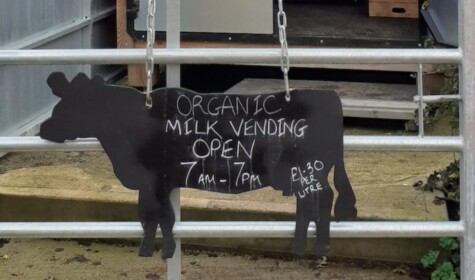

Langford Farm uses Louis Pasteur’s revolutionary invention as it was intended – as a safeguard – and employs a gentler technique than that typically used in mass production. Every few days we call in with our screw top glass bottle for a refill and my kitchen now includes a Kilner butter churner.

The marketing managers employed by supermarkets and mega-dairies want us to believe that ‘white water’ is what we desire. But the rise in farm gate sales of raw, gently pasteurised or unhomogenised milk and the increase in local delivery rounds tell a different story.