Vegetable shortages have been hitting the headlines recently, with extreme weather, rising energy costs and Brexit-related disruptions creating a perfect storm that has left many supermarket shelves empty. Here, organic farmer and SFT Chief Executive, Patrick Holden, recalls how he became a casualty of centralised supply chains and describes the changes that are needed if the UK is to produce sustainable food at scale.

I have a particular interest in the current vegetable shortage story, because I am one of the casualties of so-called ‘category management’, the term used by supermarkets to describe the cost-saving process of obtaining an increasing percentage of their supplies from ever fewer producers.

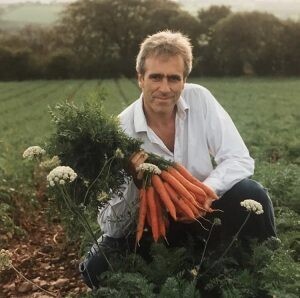

Back in 1979, shortly after I had first started farming, I was persuaded by my friend Peter Segger (himself a vegetable grower), to plant half an acre of carrots on my farm in West Wales, to see if they would grow in our western climate. We grew open pollination varieties including Autumn King and Berlicum as part of a seven-year rotation, building fertility from the grass phase of the rotation, rather than relying on non-renewable chemical fertilisers. I’m pleased to say that the carrots did really well, and I found markets for them in London at the original Wholefoods shop and Cranks restaurant.

One thing led to another and within four years we were growing a significant acreage – up to 10 acres in our peak carrot year! This led us to switch from selling into the emerging organic wholesale market to supplying Sainsbury’s and Waitrose. We printed our story on the back of the carrot bags and gained a loyal following – customers used to write to us, thanking us for being part of this sustainable story of vegetable production.

Then, after 25 years it all came to an abrupt end, after the supermarkets decided that they would move all their packing facilities to Peterborough, some 235 miles away from the farm. At this point, it became financially unsustainable to transport our carrots that far, especially since they had no cold storage facilities at the other end.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the end of our carrot growing chapter did not go unnoticed, since I was working at the Soil Association at the time. Our story was covered in a front-page Guardian article and featured on the Today Programme, much to the upset of the then Chief Executive of Sainsbury’s.

I recount all this not out of any malice towards the supermarkets concerned, but more to highlight the damaging consequences of our present centralised food system. If you analyse the origin of the vegetables that most people are eating today, if they don’t come from hydroponic systems (which is the case for nearly all the salad crops we consume in the UK), they are almost certainly grown in the east of England, in vast arable monocultures that are sprayed with an array of chemicals.

The key point about all this is that the latticework of decentralised and regional infrastructure which used to enable local food production, sale and consumption, has been largely dismantled over the last 50 years. As a result, just about all the food found in supermarkets is now not only processed and packed in a small number of facilities, often one per commodity, but also distributed through highly centralised networks. As an example, we used to sell our carrots in bunches to the local Co-operative in Lampeter; now, they would have to go to Manchester to be re-distributed, probably via a packhouse located elsewhere in the country.

There are good economic reasons why the supermarkets and food companies have taken these actions and they are all to do with ‘economies of scale’. In a world of dishonest economics, where the polluter doesn’t pay and the environmental and social costs associated with centralised food systems are not factored in, these systems make perfectly good economic sense.

As a result of all this, the actual story of where our food comes from is very well hidden from supermarket shoppers. As my friend Eric Schlosser (author of Fast Food Nation) once said, “If you knew the story behind much of the food you eat today, you wouldn’t want to buy it.” And, as the events of the last few weeks have demonstrated, it is only when shortages panic the public that the media pay attention to stories of food insecurity and damage to climate, nature, culture and health.

So how can we reverse the centralisation of our food systems? The solutions are not always simple. We need to begin by returning to farming systems which are truly sustainable and working in harmony with nature. In the case of vegetables, rather than being produced by specialised farms that are reliant upon vast packing stations and distribution infrastructure, they will instead need to find their place once again in balanced rotations which include a fertility building period, normally of grass followed by a series of crops. This should be the future story of the potatoes, carrots, cabbages, leeks and other crops which are best grown on a field scale in the UK. To complement this, the salads, leafy vegetables and other more intensive crops could be grown in horticultural systems fertilised by compost. This transition would have tremendously beneficial consequences for the environment, food security and public health.

Unfortunately, we are a long way from producing food in harmony with nature, at scale. Enabling this transition will require action at all levels – from government intervention, to support from the banking, financial and investment community, as well as retailers and supermarkets who need to ensure that consumers are given full transparency about where and how their food has been produced.

The good news is that a groundswell of interest is gathering momentum amongst millions of people who want to know the story behind their food. People are also waking up to the fact that we have a dishonest food pricing system, whereby food that appears to be ‘cheap’ is often the most costly for our environment and health.

The Sustainable Food Trust is working to redress this distorted economic environment for food and farming, by creating a common framework that defines on-farm sustainability and measures whole-farm impacts. This global measure of sustainability will allow governments to assess, monitor and support the delivery of public goods; financial services to invest in more sustainable farming; the food industry to source more sustainably and amplify transparency; and ultimately, to help the public to make more informed choices.

Each of us has the right to know how our food has been produced and where it has come from. In the short term, the efforts of those willing and financially able to opt for foods which have come from sustainable and regenerative food systems, where the costs of production have been accurately accounted for, will begin the process of driving the change that’s needed. Ironically, external events such as the Ukraine war, which has dramatically impacted energy, fertiliser and fuel costs, may even speed up the process, but we can’t completely rely on that! In the end, equipping the public with the knowledge they need to make informed choices will be essential.