The conflict in Syria and the rise of Isis have displaced half a nation of people and generated the largest humanitarian crisis in the world today. Some 8.7 million people are now suffering food insecurity, and the country’s agricultural infrastructure has largely been destroyed. Yet while ideological, political and religious differences are clearly major causes in the conflict, what often gets overlooked is the impact of climate change and agricultural policies in generating a social and ecological disaster that may have contributed to the country’s political breakdown and bitter war.

Agricultural decline

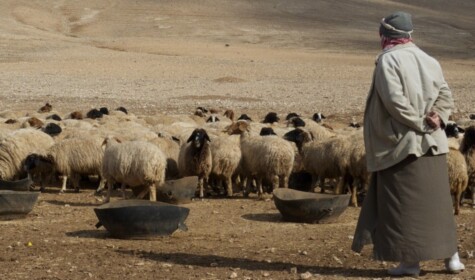

Television images give the impression that Syria’s land is little more than parched and dusty soil, and increasingly that has become the case. Yet pre-conflict Syria was seen as a ‘middle-income’ country and played an increasingly prominent role in the global food market, with a strong agricultural sector producing key crops such as wheat, barley, cotton and olives.

During a conversation with Stephen Starr, who has lived in Syria and written extensively on the conflict, he shared his view that drought and consequent food shortages were the single most important factors in setting off the revolt in 2011.

Syria suffered four consecutive years of drought starting in 2006, with 2007-2008 being the worst in 40 years. Herders lost up to 85% of their livestock and small-scale farmers could not produce enough to feed their families. By 2010 a UN official warned that drought had pushed up to 3 million people into extreme poverty. Mass migration to urban areas sparked public unrest due to greatly increased competition for jobs and resources with other Syrians and with refugees from Palestine and Iraq.

Evan Fraser and Sylvain Charlebois, professors at the University of Guelph’s Food Institute, have commented that, “Throughout history, agricultural problems have acted as catalysts that trigger widespread social and humanitarian crises.” The French revolution, for example, occurred when El Niño caused harvest failures, triggering mass rural-to-urban migration. In Syria, the drought and its impact on agriculture destabilised the country, with people flooding into cities that lacked the infrastructure to cope and where corruption and inequality became commonplace.

Climate change has been blamed for the severe droughts in Syria, and there is a growing consensus that this contributed to the initial conflict. Last year the Prince of Wales spoke out about the accumulating effect of climate change, which he says is leading to social upheaval and conflict over scarce resources in places like Syria.

According to Francesco Femia of the Center for Climate and Security, “We can’t say climate change caused the civil war. But we can say that there were some very harsh climatic conditions that led to instability.” Fraser and Charlebois agree that it is too simplistic to blame climate change for the turmoil in the Middle East, but “it is necessary to understand that unpredictable weather patterns hurt farming systems, and this was a factor in the current situation.”

But while climate change is a major factor, many Syrians do not want it to become a scapegoat for government failure. They say it was government policy that really perpetuated the problem and left Syrian agriculture unable to cope with drought.

According to researcher, Francesca de Châtel, the humanitarian crisis that followed the drought can “be seen as the culmination of 50 years of sustained mismanagement of water and land resources.” The government had been pursuing a policy of agricultural intensification and economic liberalisation based on the expansion of irrigated crops for export, such as wheat and cotton that were reliant on chemical fertilisers. The chemical inputs and monoculture cropping contributed to the degradation of Syria’s soils, while poor irrigation infrastructure led to salinisation, particularly in areas such as the Euphrates. Reliance on non-renewable resources such as chemical fertiliser and diesel makes agriculture vulnerable to price fluctuations on the global market. And with the government’s decision to cut subsidies to fertiliser, diesel, pesticides and seeds in the 2000s, many small-scale farmers could no longer afford the inputs on which their crops had come to depend.

Syria’s grazing land also struggled under intensification. Former Bedouin commons had been opened up to unrestricted grazing, turning the fragile ecosystem of the Syrian steppe, an area that covers over half the country’s land mass, into an eroded desert. In 1950 there were 3 million sheep grazing the steppe, but by 1998 there were over 15 million. According to ecologist Gianluca Serra, this damage to the Steppe ecosystem meant it could no longer cope with droughts, and this contributed to the social crisis.

The result: a humanitarian disaster

Approximately 80% of people now face poverty in Syria and food prices have sky-rocketed. In a good year, Syria could produce 4 million tonnes of wheat, exporting 1.5 million tonnes. Last year, just 450,000 tonnes was produced making the price of wheat 56% higher, according to the World Food Programme.

Bread is the staple food for most Syrians, providing essential calories and energy. With the wheat deficit, the price of bread has risen 45-95% in many bakeries. This is in stark contrast to most of the world, where there has been a major fall in the price of wheat.

Access to quality food has severely deteriorated. Families can no longer buy fresh produce and most mothers are skipping meals in order to feed their children. Even those using the WFP’s electronic voucher system have reported only being able to purchase low quality food, high in sugar and oil, and very little meat. The UN has warned that Syrian children face irreversible health problems due to food shortages.

This tragic impact is not restricted to Syria. As more than 4.5 million refugees have flooded out into neighbouring countries such as Lebanon, Turkey and Jordan, competition for resources has become an increasing problem. Trade has also been disrupted for these countries. Before 2011, it cost between $1,000 and $1,500 to transport a truckload of produce from Lebanon through Syria to the Gulf. This price had tripled by 2013, and willing drivers are hard to come by.

Food as a weapon?

Adding to this humanitarian crisis, both government and opposition groups have used food and agriculture as a tactic in the conflict. All factions understand that controlling food supply brings power. According to foreign correspondent Annia Ciezadlo, “Strategically, bread is as important as oil or water.”

In a strategy that’s been called ‘starvation or submission’, sieges are imposed on cities to cut off resources. More than 30 people have starved to death in Madaya since December as a result of a blockade. There are many more similar situations, such as Daraya where it is feared a three-year siege will also result in starvation.

Scorched earth policies have been used to intimidate civilians and distract fighters. Agricultural land around Kobani was targeted by Isis in June 2015 where some 4,000 acres of crops and fruit trees were burnt to the ground.

Control of wheat has become a central strategy for all factions, with battles at every point in the production chain. Isis has targeted Syria’s ‘bread-basket’, capturing swathes of wheat-producing land. Recognising the importance of food supply, they took over flour mills and set up an agricultural bureau to distribute and trade the grain in Syria and Iraq. Their ability to supply food has won them some support amongst the population, but they use it strategically, providing food to supporters, while limiting supplies to opponents.

Food has also been central to the group’s propaganda machine, which depicts an idyllic life for Muslims under Isis controlled areas. One dispatch last August showed a group of prosperous-looking farmers with the caption: “The civilians of the caliphate prevail in agriculture.” In conflict situations food and farming often take on a deeper meaning, symbolising longevity, prosperity and strength.

Future food security

The future of Syria’s food security has been dramatically undermined by conflict, which has devastated irrigation infrastructure, displaced farming populations, disrupted trade and caused enormous ecological damage. According to the FAO, “Syria’s food chain is disintegrating – from production to markets – and entire livelihood systems are collapsing.”

But as the crisis looks set to continue, what can be done to limit the damage and preserve Syria’s agricultural capabilities for the future?

The FAO advises that, “a resilience-based approach is proving ever more crucial to meet immediate needs while helping affected populations – and the systems which support them – better absorb, adapt and recover from current and future shocks emanating from the crisis.”

Moving away from intensive agriculture, over-reliant on irrigation and chemicals, would be an important step in preserving Syria’s ecosystem and therefore its ability to produce food without degrading its resources. Land restoration, resource protection and climate resilience should be seen as part of a peace-building strategy. As the government’s free trade policies and lack of adequate resource management appear to have contributed to the current crisis, reclaiming degraded pasture and involving local communities in land management decisions will be key to ensuring future stability. In particular, farming in ways which help to rebuild soil organic matter and make crop production less reliant on the region’s finite water resources should be a top priority.

As the Prince of Wales has said, we have been dealing with these issues in a short-term way, “leaving the underlying root cause” of what mankind is doing to its natural environment neglected. With the impact of climate change likely to increase, the demise of Syrian agriculture proves a chilling example of how quickly and how tragically food security can be undermined.

Featured image courtesy of Joel Bombardier.