Since closing our egg business, I’ve had to look for work off the farm. It’s very common for farmers to have an off-site job to support the farm business. In our case, we’ve decided to step back entirely from commercial agriculture, for now, in order to regenerate ourselves after what has been an intense seven-year period of work on the farm. You could say I’m on a ‘sabbatical’, but instead of taking time off, I’ve found manual jobs locally to keep the money coming in – while still allowing me the time and space to step back and explore new ideas.

This summer I started brush cutting Himalayan balsam for the National Park. As an invasive weed, it outcompetes native plants for both sunlight and pollinators, quickly taking over large areas of land. Then in the winter, it dies back leaving nothing but mud in its place. As a result, riverbanks deteriorate and valuable soil is lost. It’s physical, noisy work but it’s meaningful – and for eight hours a day, I get to let my mind wander, without any other distractions – no social media, no phone calls.

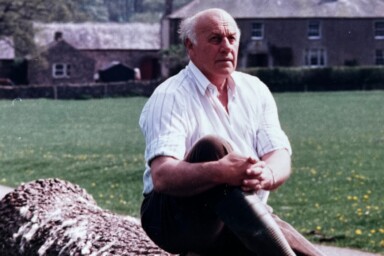

As I traverse through local farmyards in search of balsam in the Welsh countryside, I can’t help but draw a parallel between what has happened to agriculture, and what is about to happen to white collar city jobs. If you’re not familiar with the classic farmyard, some really do look like the perfect set for a post-apocalyptic film – piles of stuff which has never been thrown out as it might one day be useful, and old obsolete machinery with trees and shrubs growing through it. You’re lucky if you see a person, and unlucky if you come across a pack of dogs. The people you do see, have years of hard work written all over their faces, but they are generally happy to see you – there are far fewer people in the countryside, compared to urban spaces.

The thing is, I’m doing the work that big machines cannot – getting into all those awkward (but often beautiful) spaces. The Himalayan balsam spreads millions of tiny seeds that reach every nook and cranny of hedges and wild scrubby areas, which means that humans (often in combination with a handheld machine) are the most practical way to tackle the job. In large open areas they use robot mowers, modern machines that can traverse uneven and sometimes very steep ground, chopping up everything in sight, covering much more ground with a fraction of the manpower.