Sustainable food writer, David Mckenzie, takes a closer look at the potential for more resilient wheat production in the UK through enabling regenerative, low-input farming systems.

Whether in bread, biscuits, cakes, through animal feed or as a food and starch additive in an estimated one-third of all products on supermarket shelves, the UK consumes about 15 million tonnes of wheat a year, accounting for about 20% of the total energy and protein intake for the British population. A lot of this wheat is grown in the UK, with roughly 80% of this demand met through domestic production.

Brits eat a lot of wheat. Yet the system that supplies most of that wheat has been creaking along for a while now, exposing the fragility of this system to a wider public. Rather than bringing more doom and gloom, however, this exposure may actually provide an opportunity. It could be a chance to reset the norm – to move away from a conventional system overly reliant on synthetic inputs and their volatile prices, and instead commit to changing Britain’s wheat supply for a better, more resilient and more sustainable future.

That sounds pretty rosy. However, that “roughly 80%” figure – termed the ‘production to supply ratio’ in official government reports – has sharply declined for each of the last three recorded years, from 87% in 2019, to 81% in 2020, to 76% in 2021. That means that the UK has become progressively reliant on wheat imports in recent years. Although politics have played their part, and harvests naturally go up and down from year to year, the main reason for this is that Britain’s conventional wheat farming system is not, broadly speaking, properly set up to deal with the unpredictability of a changing climate.

Simply put, the system is too reliant on a narrow range of modern breeds of high-yielding, low-nutrition, conventional wheats, which require high levels of synthetic inputs. As many people have been saying for a while, things have to change. Yet despite ongoing awareness, and at least nominal acknowledgement from government, over the past decade, progress has been slow. However, the dramatic events of 2022, in particular, could be the spark that finally helps things change on a much larger scale.

In February of last year, the world’s largest wheat exporter invaded the world’s fifth-largest wheat exporter, essentially tying up about a quarter of the world’s total wheat market, in a political crisis. Pictures of Ukraine’s wheat-laden cargo ships, blockaded and trapped in the Black Sea for months, were some of the most striking early images of the Russian war. Naturally, concerns about flour and wheat shortages became standard water-cooler conversation in the UK, much as in the initial, home-baking-crazed months of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

To make matters worse, the summer of 2022 then saw extreme weather in the UK. Temperatures above 40°C were recorded for the first time ever, during an extended drought that caused anxiety and concern about what it would mean for grain harvests later in the year. For many Brits, this drought was the first close-to-home wake-up call to the climate crisis, and it got people wondering, or worrying, what it might mean for the security of wheat and flour supplies in the UK.

In the end, things did not end up as disastrous as first feared. The UK imports very little, if any, wheat from Russia or Ukraine; and although the drought certainly made it a tricky and uncertain harvest for a lot of farmers, there were ultimately enough pockets of rain that total wheat harvests were not too depressed, overall.

Still, that’s not to say that UK wheat production was unaffected by those major events of 2022 – far from it. Although the supply of wheat in the UK may not have been severely disrupted by the war in Ukraine, something else certainly was: the price of wheat. The main reason for this is the price of key inputs – especially nitrogen fertiliser, which skyrocketed to all-time highs during 2022.

The vast majority of wheat produced in the UK is grown in conventional, or ‘non-organic’, systems. These systems rely heavily on synthetic inputs (such as fertiliser and pesticides) to ensure reliable, high yields from modern wheat varieties bred for the purpose. By far, the most widely used input in the UK is nitrogen fertiliser, to the tune of about 1 million metric tonnes per year. Russia is the world’s largest exporter of nitrogen fertilisers, and it dominates the global market for natural gas and other key components in fertiliser production. Unsurprisingly, then, the Russian invasion of Ukraine (and the UK’s subsequent implementation of sanctions on Russian imports) had huge impacts on the price of fertiliser for UK farmers. At one point last year, the price of nitrogen fertiliser per tonne was nearly three times higher than the already-record high from the same period a year earlier in 2021.

For years, the high yields, relative affordability of inputs and reliable performance of conventional grain growing has made it hard for farmers to transition to more sustainable practices. However, the sky-high price of fertiliser and other inputs – combined with the uncertain conditions of the extended drought, heat and dryness, which brought with it significantly increased fire risk around combine harvesters – made 2022 an anxious growing season for many conventional farmers. Decisions that these farmers usually have to consider, like whether to apply fertiliser late in the growing season to boost grain protein content, became much more difficult to make.

The fertiliser-cost crisis, of course, didn’t go unnoticed. In June of 2022, the Government responded to it with the publication of a Food Strategy announcement. This followed from an earlier Defra press release (in March 2022) and was in lieu of an official update to the UK Food Security Report, which was last updated in December 2021. The June 2022 “Food Strategy” announcement, rather confusingly, reiterated both the introduction of the Sustainable Farming Incentive – aimed at “reducing reliance on manufactured fertilisers” – while also, paradoxically, pledging to “work with industry to develop plans to bolster resilience of critical inputs” like fertilisers. The March press release also announced a delay on the Government’s own climate-friendly plan to phase out the use of urea fertiliser over the next decade, as part of the UK’s pledge to reduce carbon emissions and restore its degraded habitats and ecosystems.

These documents display a clear tension in what the Government and farmers – and many of us, really – are trying to do. On the one hand, we are ostensibly trying to move towards more regenerative, sustainable, climate-friendly farming systems that are better for our land, our planet and our bodies. On the other hand, though, there are a lot of bad habits and big businesses (with their profits and employment prospects) standing in the way, and it’s often easier to resort to short-sighted, quick-fix solutions – especially when it’s getting harder and harder to pay the bills. Many conventional farmers are just trying to make ends meet.

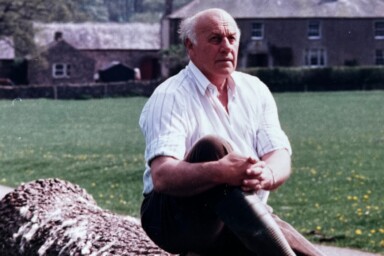

This is a tension that has been observed by Gerald Miles, an organic grain farmer near St. David’s in Pembrokeshire, South Wales. For the past two decades, he’s been plugging away with his low-till, no-input system of growing a number of heritage grains, local landrace varieties and organic wheats, being careful to protect and replenish the health of his soils with diverse rotations. His neighbours, meanwhile, have all played the conventional game, using synthetic inputs and modern varieties to get reliable yields.

“With climate change knocking on the door,” Gerald says, “British farming and food production is at a turning point.” Several months into 2023, the tragic war and occupation in Ukraine is still ongoing. And although the Russia-UN Black Sea Grain Initiative deal has helped to free up Ukraine’s grain exports, and fertiliser costs have dropped slightly from their astronomical highs of last year, costs are still historically high. This isn’t only about Ukraine either, as volatile, unpredictable prices are becoming more and more common. “The conventional growers”, says Gerald, “have been really struggling with price hikes over the past few years, and they are being forced to look into transitioning towards lower-input production for the coming seasons.” As a result, many of Gerald’s neighbours – having shown little interest in his ways for years – have been asking him how to go about it.

Luckily, Gerald is not the only one around to ask for help.

In Shropshire, Mark Lea of Green Acres Farm grows a wide range of organic grains, both heritage and modern, on a sizable commercial scale. He says that these wheats, with their long stalks, deep roots and natural abilities to “scavenge nutrients” and compete with weeds, coped and performed well in the extreme conditions of last year. Meanwhile, many conventional grain farmers in the area saw their crops die back early, before completing their full maturation and development stages. This rushed the harvest well forward, potentially affecting grain quality and protein content, a key aspect for selling wheat on today’s market.

Such a knack for heritage grains doing well in difficult times, without artificial inputs, has been backed up by scientific trials carried out by the National Plant Phenomics Centre (IBERS) at Aberystwyth University. Since 2019, IBERS have been growing trial plots of Hen Gymro, a traditional Welsh landrace, in different conditions and altitudes in a no-input system, in order to assess its resilience to changing climatic conditions. Last year, according to Dr Fiona Corke of IBERS, the plots of Hen Gymro really thrived, despite the abnormal weather. Meanwhile, the modern wheat varieties – grown alongside the Hen Gymro in exactly the same soil – withered away in the dryness, and “looked particularly poorly” without the synthetic nitrogen boosts for which they are bred.

These are only a few random examples, and there are many similar growers, agronomists, millers and associations (like the fabulous Brockwell Bake) working hard around the country, setting examples for what Britain’s more resilient wheat production system could look like in the future.

The pieces are all there: there’s already government legislation in place that acknowledges – at least nominally – the need to support more sustainable farming initiatives (and provide more concrete incentives for farmers who are trying to do so). There’s also growing willingness among conventional growers to look into transitioning to low-input systems, often pushed by cost pressures and/or encouraged by the examples set by their neighbours. And there’s increased scrutiny from the general public about where their food, specifically flour, comes from, and why it might suddenly disappear from shelves from one day to the next.

For that reason, despite all the anxiety, uncertainty and fear that 2022 may have provoked for many wheat growers (and bread eaters), it could be a real wake-up call. Maybe, it will ultimately be looked back upon as the year that finally shoved British grains onto a more resilient, sustainable path.